Investigative Stories

Dil Bahadur Ramtel of Manthali Municipality-8 is doing the dishes, seated at his porch. Nearby lies a walking stick—the only support for his frail body, literally and figuratively, as his wife passed away years ago and his children live elsewhere. Dil Bahadur’s four daughters are already married and his three sons live in Kathmandu, where they run businesses. They come back to the village only during the festivals and hence, Dil Bahadur, who is 63, is often alone at home.

Two years ago, Dil Bahadur went to Kathmandu, to live with his son and daughter-in-law. But he couldn’t stay there for more than six months. He found the capital city’s atmosphere “suffocating”, he says. “They loved me but I did not feel at home in the city,” he adds.

So Dil Bahadur returned to his own, lonely place.

The home adjacent to his is empty. And so is the one above his. While many houses built after the earthquake in this village are in good shape, they have no inhabitants. Such is the irony Dil Bahadur confronts every day.

“Back then, houses were few but they were full of people. It was fun to go to the farms,” Dil Bahadur says, adding that the 2015 earthquake changed things. “The government provided Rs300,000 in compensation to those whose houses were damaged. Many built houses with that money but they didn’t live there. They began to migrate to Kathmandu.”

But not just Kathmandu, many youths also went to Madhesh and abroad for work. “I wonder if anyone would remain in this village after a couple of years down the line or so,” Dil Bahadur says.

Among those who migrated to Kathmandu after the earthquake are the son and daughter-in-law of Makar Bahadur Karki, who is resident of Gokulganga in Ramechhap. After a while, they invited Makar and his wife to their rental room in Suryabinayak, Bhaktapur. But like Dil Bahadur, the Karki couple also felt ill at ease with the city’s atmosphere. They then returned to the village after six months. They cleaned the house, and started farming again. They even send the yields to their children in Kathmandu.

But over the years, the couple grew frailer and they stopped farming. They sold their livestock and are now dependent on their son. “They sometimes send us money and rations,” Karki, who is 73, says. “Sometimes, they even send us the meat they had cooked.”

No sales at shops

Until a decade ago, the Joshi General Grocery Store at Sunapati Rural Municipality-3 in Ramechhap used to teem with customers. The store got used to get even more crowded during the six months after the earthquake in 2015. But gradually, the store began to see less and less customers as it felt the pinch of out-migration.

“We used to sell over 50 sacks of rice. And about 20 sacks of lentil,” Raju Joshi, proprietor of the store, says. “Now we hardly sell 5-7 sacks of rice. And just about a sack of lentil.” A decade ago, when the store was booming, Joshi had four staffs with all of them so busy and would hardly get time for lunch. Now he has single staff.

Many people from Ramechhap, which lies a 139-km road travel away from Kathmandu, have migrated to the three districts of the Valley. Most of them are youths, staying in the Valley for studies or for jobs. They send the market goods from city and even send daily essentials to their families back home. This is one reason shops in Ramechhap have seen declining sales, says Uddhav Karki, from Gokulganga. “The district has a thinning-out population and they rarely purchase goods from local shops,” Karki says. That they receive even vegetables, rice and corn from Kathmandu often makes Karki wonder if time is running backwards.

Nawaraj Pathik, a journalist based in Ramechhap, says foreign employment is driving the disconnect between agriculture and villagers. “Most houses receive remittances from Malaysia and the Gulf countries,” Pathik says. “Farmlands are left fallow. Cowsheds and chicken barns are demolished. Villagers buy green vegetables and chicken from Manthali [the district headquarter] while it should have been the reverse.”

Dil Bahadur Ramtel of Manthali says that due to thinning out population, even the monkeys have begun to mock the humans. Ramtel says he struggles to save the beans on his farm. Due to a shortage of manpower and monkey menace, his 62-ropani farmland has remained fallow for the past five years, he says.

“My son and daughter-in-law send me money to buy the crops,” Ramtel adds. “And they bring me clothes when they come.”

Transport sector feels the pinch

The Araniko Yatayat has been operating on the Kathmandu-Ramechhap route for about 30 years. The Yatayat’s buses would be packed back then, with people even climbing to the hood for travel. But with time, the number of travelers began to dwindle and the buses began to run on with vacant seats.

The Araniko Yatayat has 40 buses that ply daily along Kathmandu-Banepa-Ramechhap-Okhaldhunga-Dolakha route. While a bus has 31 seats, only about 15-20 are filled usually, according to Subas Phuyal, the Yatayat’s Ramechhap in-charge. “These days, it takes either festivals or any other such significant occasions for our buses to get full of passengers,” he says.

Kedar Panta, an official at Araniko Yatayat’s Chabahil counter, says that they often merge passengers from two-three vehicles into a single one. During the ten years that Panta has been working with the Yatayat, there has been a 30 to 35 percent decline in passenger numbers, he says. “Had the population in village remained same as past given that there has been increase in roads, we would have to add 20 more bus. But the passenger numbers are on the decline,” Panta adds.

Empty houses, lifeless villages

According to the census of 2021, Ramechhap had a total of 82,083 houses. Of them, 17 percent, or 14,042 houses, were without inhabitants. Currently, one in five houses in Gokulganga and Khandadevi are without inhabitants.

Last year, the Manthali Municipality conducted a survey to understand the condition of infrastructure so as to declare the local government a ‘children-friendly’ one. The survey revealed only 9,590 houses were inhabited by people. “We are surprised,” says Mayor Lawa Shrestha. “We didn’t think so many houses were empty. Even the municipality that has the headquarter of the district is out of people. We can’t imagine how it is in the rural areas.”

The national census of 2021 had shown the municipality had a total of 18,772 habitable houses. Of them, 2,727 were without people. During the three-year period between the census and the survey, half of the houses were emptied out.

Shambhu Shrestha, former chair of Ramechhap chapter of Federation of Nepalese Chamber of Commerce and Industries, says as much as 75 percent of houses in the municipality are peopled only by the elderly. As much as 25 percent of houses are without inhabitants.

According to Shrestha, who has been running a shop at Ramechhap Danda for about 30 years, the Maoist insurgency led to the start of the migration trend. People began to migrate to the headquarters to save their life and didn't return to the village.

The war-affected then migrated to Kathmandu. While the war came to an end in 2006, the fear remained. “Many people had already envisioned a future in the city by then,” Shrestha says. “And they didn’t return to the village. Instead, they called their relatives and neighbors to the city as well.”

The Dware Tole in Manthali’s ward 8 is a migration-affected village. Of the 25 houses, 15 are empty now. “If previously, villages were alive with people, now there’s only emptiness,” Kishori Shrestha of the village says. “We don’t know where and how this migration trend will end.” The village life which included cattle grazing, farming, fetching water and gathering together have become things of the past.

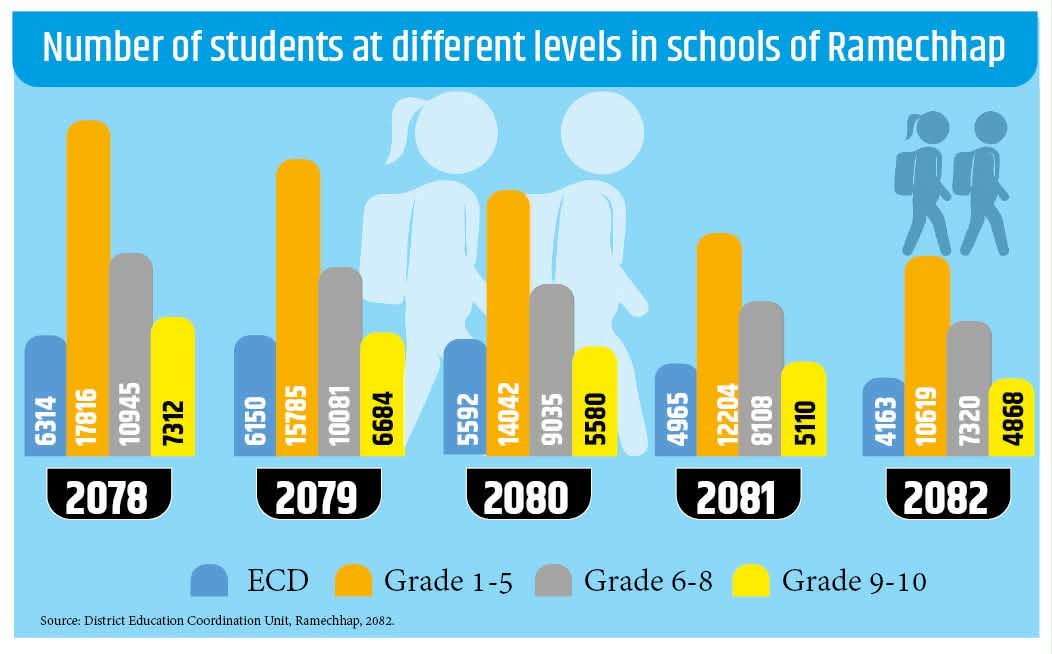

Forty schools shuttered

The impact of the migration is also apparent in the schools. In 2078 BS, as many as 42,378 students were enrolled from pre-primary up to secondary level. Four years later, in 2082 BS, the number declined by 29.27 percent. Two years ago, the Setidevi Secondary in Gokulganga had 300 students; now, it has only 116.

In Bhalepokhari, Kushmawati and Mahadevshwari primary schools, classes are run only up to grade 3 and there are no students in grades 4 and 5. In the other two schools, classes are run up to only grade 1.

In Likhu Tamakoshi Rural Municipality, up to 200 students are declining every year. The rural municipality had 4,800 students in 2076 BS and 3,740 in 2081 BS. “The number of students declined by over 1,100 in five years,” Jaya Krishna Chaulagain, chief of the rural municipality’s education department, says. “There’s no hint of a rebound no matter how much of a quality education we would provide. Migration has become a compulsion for the people. Meanwhile, the birth rate is also on the decline.”

The decline of student numbers has led to shuttering of schools, reports Ramechhap district education coordination unit. According to the unit’s data, as many as 40 schools were closed this year due to lack of students. Dinesh Nepali, the unit’s technical assistant, says over 100 schools have less than 20 students each. “Migration is the primary reason,” Nepali says. “The second reason is the decline in birth rate.”

Statistics from health posts show the rapid decline in birth rate in the district. The Pakarbas Health Post in Khandadevi Rural Municipality saw 49 births in fiscal year 2079-80 BS; the number came down to 36 in 2080-81, and to 26 in 2081-82. The health service department had supplied medicine and surgery equipment for an estimated 22 newborns in the local unit’s ward 5 last year but it saw only five births.

The birth rate has decreased significantly. “Youths no longer live in villages and those who live do not want to have more than two kids,” health assistant Nawaraj Shrestha says. “Youths population are abroad due to out-migration and those who can travel to Kathmandu for the delivery.”

The District Hospital Ramechhap saw 161 newborns in three years, which came down to 127 and 128 in the subsequent years.

The absence of youths has also led to a shortage of teaching staff in the villages. Schools are struggling to recruit teachers for the subjects like math, science, and English. Setidevi Secondary School at Gokulganga-9, Chuchure and Brikheswor School in Likhu Tamakoshi had to announce vacancies for multiple (up to 7) times to recruit math teacher.

Local government deal with multiple problems

With the population declining, it’s been hard to form users’ committees and run community programs.

The Ramechhap Municipality launched the Housemakers Empowerment Program funded by the Bagmati Province Government last year. The program, which sought to provide young women with skill-based training, should have had 15-30 women between the ages of 20 and 55 in a group. The municipality had aimed to form 15 groups but it ended up forming only 9 because there were not enough women, according to Sarita Budhathoki, the facilitator of the program.

The municipality does small-scale works of infrastructure development through the users’ committees. Only those below 60 years of age can become the members of the committees. But few people below 60 remain in the village, says deputy mayor Balkumari Karki Thapa.

Manthali’s Mayor Shrestha says that municipality is facing problems due to a lack of people of the target age group. “Most people in the district divide their time between Ramechhap and Kathmandu,” Shrestha says. “And they don’t like to bear the burden of the consumer committee’s work.”

Ramesh Subedi, an official at the municipality’s women, children, and social welfare department, was the secretary of ward 9 until a year ago. Subedi says that once, when they sought to gather people to form a consumers’ committee for a project, they had expected 70 people. But only 14 showed up. “And some of them were already in other user groups,” Subedi says. “This breaches the regulation. And so does keeping more than one member of a single family in the same users’ committee.”

The impact of migration in the villages is so much so that the local governments have to go to Kathmandu Valley to distribute social security benefits. In September, Ramechhap Municipality’s wards 7 set up camps in Kathmandu and Bhaktapur to distribute social security benefits.

Mayor Neupane says that they had to set up the camps in the cities to avoid the misuse of social security benefits as the biometric system has come into effect from this year. “People haven’t migrated officially but they no longer live here. They are registered voters from here,” Neupane says. That’s why we have to travel elsewhere to provide services to them.”

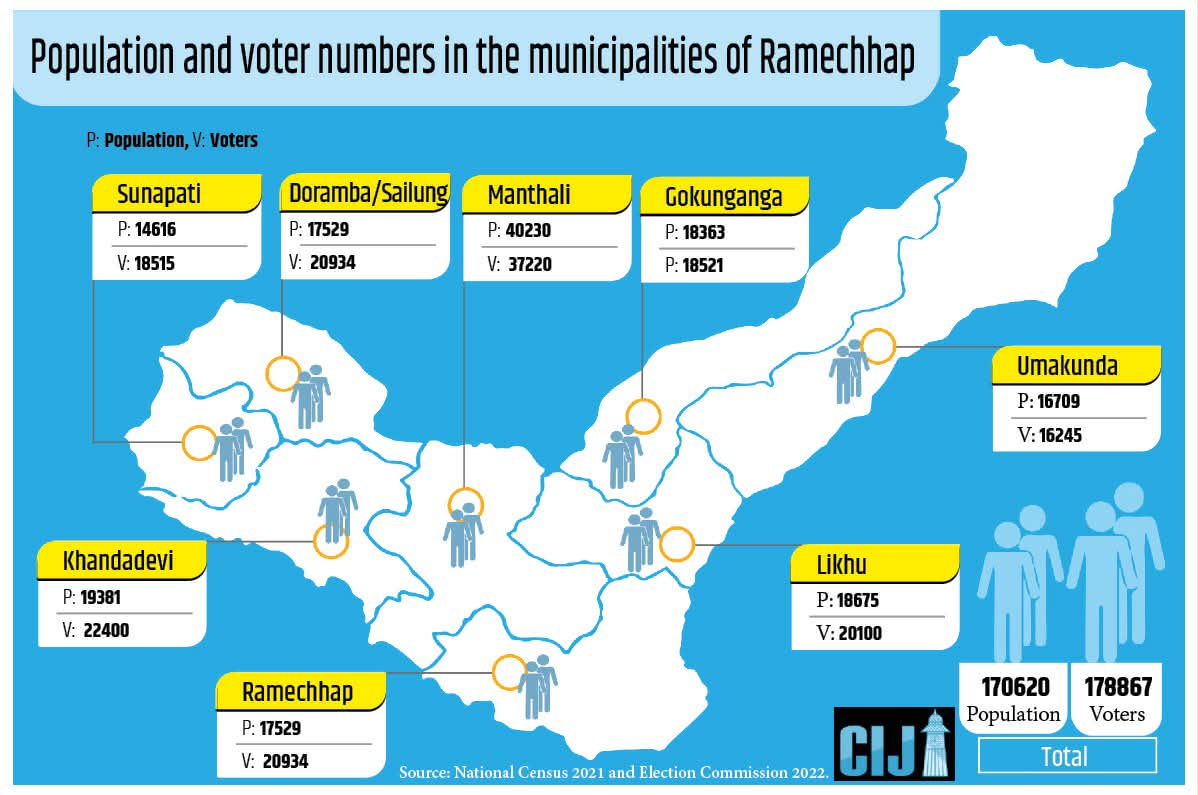

More voters than the population

Migration has created a surprising statistic in Ramechhap. According to the 2021 census, a total of 170,620 people lived in the district. But a year later, during the general elections, the number of voters was 178,867. The number of voters exceeded the population. Except for two municipalities, the surprising statistic was apparent in all six rural municipalities.

Dhundi Raj Lamichhane, spokesperson of the statistics office, says that census counts people where they live for more than six months. But voters’ roll includes names based on their permanent residence. Moreover, the voters’ roll could also include people who have migrated abroad or are dead.

In Nepal, 7.5 percent of the population is abroad. Meanwhile, in Ramechhap, 11 percent people are abroad, according to Lamichhane. And this number is not included in the total population of the district. Hence, Ramechhap, along with Manang, is the district where there are more voters than the population.

According to Ramechhap Municipality Mayor Lawashree Neupane, many people who are absent in the district haven’t officially migrated. “Their names are on the voters’ list until they formalize their migration,” Neupane says.

Meanwhile, political leaders say that because people who have migrated return only to vote, the election results are often unprecedented.

Why the villages emptied out

After they didn’t get jobs, and desired quality of education and health facilities, residents of Ramechhap began to descend to Kathmandu and Madhesh, while some others went abroad. Ramechhap is in itself a dry district that doesn’t receive much rain. Of the district’s 61 wards, 24 are declared ‘drought-stricken’.

“Rice doesn’t grow in this place,” says Madan Achhami of Manthali-8. “The only crops that grow are maize, millet and Masyang. There’s Koshi flowing down below. But our lands remain fallow.”

Achhami adds that many people migrated to escape this struggle for food and irrigation. “But Achhami’s neighbour, Kalu Bhujel, 75, says there's been no drinking water problem in the village for the past 7-8 years. The irrigation problem, however, remains intact.

“Our main diet was corn grits [chyakhla] and horse gram [gahat],” Achhami says. “People had endured too much hardship, so when the opportunity arose with roads, they moved out.”

As per the Mayor, Ramchhap Municipality office has tried to lift water from the Sunkoshi River in the basin to the hills to solve the drinking water problem.

The stone apple factory, which had opened 28 years ago and subsequently closed, is an example of just how dangerous the drought in this region is. To utilize the stone apple fruits that are found in abundance in the district, the Federation of Community Forest Users started the Tamakoshi Forest Product Processing Pvt Ltd in the late 90s. But the stone apple trees couldn’t endure the drought and died one by one. The factory then closed.

“The drought is one of the main reasons for migration out of the district, although the frequency of rainfall has increased in later years” says Gyan Bahadur Khadka, chair of the federation.

Harichandra Mahat, who teaches at Bhungeshwar Secondary School in Likhu Tamakoshi Rural Municipality, says that people couldn’t produce enough food through farming and there were no jobs, hence they moved out. “The youths moved abroad,” Mahat says. “And many others sold what they had in the village and moved to the cities.”

Mahat adds that those who have run livestock and poultry farms in the village are fed up from bureaucratic hassles while also attracted to foreign employment. “I met a neighborhood brother in a queue at the bank a few months ago,” Mahat says. “He was there to close his farm’s bank account and move abroad.”

Taley Nepali, who has been running a tailor shop at Manthali Bazaar for four years, is also preparing to fly abroad. After his shop couldn’t make enough returns on the Rs1 million investment, he was looking for options. “My business is about to go bankrupt,” Nepali says. “What do we expect when there are no people at all?”

Is there a silver lining?

Kaji Bahadur Khadka, chair of Gokulganga Rural Municipality, says migration is natural as people tend to move wherever there is promise of progress. “This is human nature,” he says. “But while people have moved from here, we should have attracted another set of people to our place. But the local governments don’t have the capacity to do that.”

Meanwhile, Bharat Tamang, who reached Kathmandu from Ramechhap ten years ago and started living there, says that unless people get employment in the villages, the migration trend wouldn’t stop.

In May, Shiva Shakti Neupane, ward chair of Likhu Tamakoshi-7, submitted a memo to then prime minister KP Sharma Oli to stop migration from his village. The memo requests the prime minister to suggest ways to stop the out-migration and make bank interest rates cheaper so youths could take loans and start agri-businesses.

Meanwhile, the Manthali Municipality introduced a policy to encourage people to give birth to a third child, with aims to balance the declining birth rate, according to Mayor Shrestha.

For the past three years, the municipality has been sponsoring the studies of 14 students who choose science and math streams for their higher secondary education. In return, the students have to teach at schools designated by the local government for at least six months after they finish their studies. “This policy aims to counter the lack of teachers in those subjects,” Mayor Shrestha says.

The first decision Gopal Shrestha, ward chair of Manthali-8, made after he was elected in 2022 was to stop providing migration certificates. Shrestha says that that extreme step was taken after the ward couldn’t control migration despite various efforts. “I try to convince those who come to take a migration certificate to stay at this place,” he says. “I only provide migration certificates to those who are really compelled to take them. Otherwise, I try to convince them to stay back.”

Shiva Prasad Neupane, ward chair of Likhu Tamakoshi Rural Municipality-7, has adopted a similar approach. “If we provide a migration certificate to everyone who chooses to move out, there would be no one left in this ward,” Neupane says. “But for those who really need it, we oblige.”

Amid this, Ramechhap Municipality has decided to provide a 50 percent grant to farmers who choose to buy water buffaloes. The local government has disbursed Rs3.7 million for the provision, introduced last fiscal year. “We believe that the scheme has prevented at least a few dozen youths from flying abroad,” deputy mayor Bal Kumari Karki Thapa says. “Maybe the migration trend would be mitigated if all local governments adopted a similar approach to keep youth engaged?”

Mayor Shrestha, however, doesn’t believe that the scheme would be enough to mitigate migration. He adds that since Kathmandu is not so far away, there would be no shortage of markets for local produce. “But a small effort would go only so far to control migration in this age of globalization,” Shrestha says.

‘If there are no people, who would we do politics for?’

A large number of people have migrated from Ramechhap. Why is that?

Ramechhap is known as a district that has the highest rate of out-migration in the country. We have yet to find out the exact reason behind this. It might be because of better education and health facilities and job opportunities elsewhere. If we look at those who have migrated from the villages to district headquarters Manthali, they have come to educate their children, for better health facilities and to escape wildlife attacks, among other reasons.

On the other hand, a large number of youths have moved abroad as that has become a trend nationwide. Those who have some capital have moved to Kathmandu to educate their children in better institutions. During our time, we used to walk for three days to fetch kerosene from Sindhuli so we could study during the night. Now there’s electricity at every home. And that has not been quite sufficient.

Now the education quality in the villages is decent enough. But parents do not trust public and community schools as even government employees, teachers and people’s representatives enroll their children in private ones. So, the general public do not trust in the education provided by the government through public schools. This has been the dominant public psychology, which has driven out-migration.

Migration is a global phenomenon, it happens everywhere. But there’s also the possibility of new people arriving.

You are right. People from Australia may migrate to the US. Those from Canada go to Europe to search for better opportunities. Those from Europe go to Australia. This cycle continues. Possibility ignored by one may be apparent to the other. I had been to South Korea some time back. A large number of people moved abroad from that country as well. But a large number of Nepali youths move to Korea for work.

But we don’t have such an environment that could attract people to our villages. People from Ramechhap moved to Kathmandu or Bardibas but we couldn’t attract those from Sindhuli or Khotang to Ramechhap. Those from Mahottari and Dhanusha didn’t see any opportunity in Ramechhap. As long as migration is one-way, it creates imbalance in population density.

How could the ongoing trend of migration be stopped?

Ramechhap is a drought-stricken area. It receives very little rainfall. If we hadn’t been able to pull water from the Sunkoshi River down below, the migration problem would be worse still.

But the water drawn with the lifting technology is expensive. So, people have chosen to just migrate instead of bearing all those hassles. People are increasingly quitting agriculture as it requires much labor work. Instead, they search for work elsewhere.

The population is in decline. But the local governments are unable to mitigate the migration trend. Migration can be mitigated to some extent if there are industries that provide jobs to 50-60 people in a ward.

After India imposed a blockade, many people returned to the villages and began to re-engage in agriculture. The coronavirus pandemic led to a similar trend of people coming back home. But once the dust settled, people began to move out.

People’s needs are infinite. So, people are migrating to fulfil those needs and ambitions.

Were there any warning signs this situation was in the making?

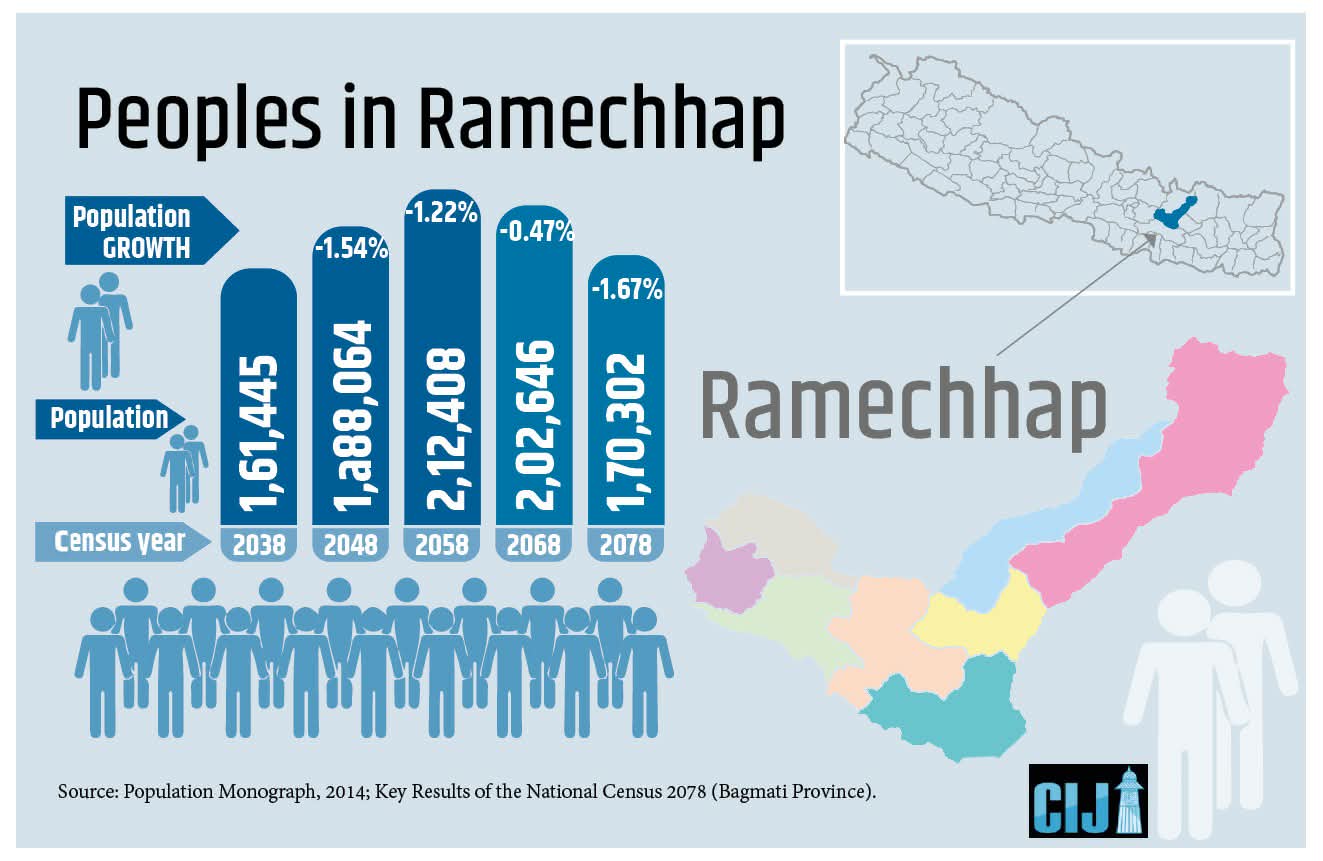

The warning bells had rung as far back as 20-22 years ago. The armed insurgency led by Maoists gave a rise to the trend. The census of 2001 had shown the sudden decline in birth rate in the district. It declined further as shown by the census a decade later. And in 2021, Ramechhap was the district with the most rapidly declining population in the country. What I mean is, there should have been a policy in place to address the trend two decades ago.

The federal government should come up with a policy to control migration from the hill and Himalayan region and manage population in Tarai and the cities. If the current trend of migration continues, there's a risk that all the villages would be emptied out soon. If there are no people, who would we do politics for?

More Investigative Stories

Hotter Himalaya melts glaciers

Villages in Manang live directly below a glacial lake that is in danger of bursting

Stray cattle continue to haunt Kailali and Kanchanpur streets despite massive investment to manage them

Streets and settlements in Kailali and Kanchanpur have been teeming with stray cattle for years, destroying crops and causing road...

Comment Here