Investigative Stories

Until about 30-35 years ago, Thagu Jogi (Tharu) of Gauriganga in Kailali had as many as 17 cattle in his cowshed. Cows and buffalos would produce milk while bulls and oxen would be used to plough the farms and pull the carts. Their manure would provide organic fertilizer for the crops.

Things have changed. These days, farmers in the district don’t have cattle. And they depend on chemical fertilizer to grow crops.

Many farmers have freed their cattle. And these stray cattle have posed a threat to the crops grown on their farms. They have increased road crashes. Roads have become littered with their dung. These homeless cattle have become a headache for not just the local residents but also law enforcement authorities, local governments and farmers alike.

Data from Sudurpaschim Province Police Office shows that in the past five years, as many as 10 people died and 24 have been injured in road crashes caused due to collision with stray cattle in Kailali and Kanchanpur.

Dambar Bahadur Biswakarma, the then chief of Province Police Office Dhangadhi who is now the AIG of Nepal Police, says that herds of cattle causing road crashes in the nighttime is a recurring incident. “Stray cattle have also been causing traffic jams of late,” Biswakarma said.

Meanwhile, farmers are also fed up with stray cattle as they damage crops. “We have to keep vigil the whole night to keep the crops safe,” said Ramesh Bhat, a farmer from Mahadeva in Kailali’s Gauriganga Municipality. “These days, we only do subsistence farming. For commercial farming, we have to spend a lot to keep crops safe.”

There are about 2,970 stray cattle in Kailali, according to a 2081 BS study by Veterinary Hospital and Livestock Service Expert Centre, Dhangadhi.

Why are the animals freed

The ten-year-long Maoist insurgency led to a rapid outmigration from Nepal’s villages. Those who could move abroad and others migrated to city centers. Farmers among them untethered their cattle and moved out.

Around the same time, the trend of turning national forests into community forests was all the rage. Grazing grounds and open spaces with flora and faunas were also included in the area of community forests. Meanwhile, grazing cattle in community forests was prohibited.

This compounded the problems of the farmers, who were already dealing with issues such as shortage of human resource, struggling to purchase modernized agriculture tools such as ploughing machines. The cattle in the cowshed only added to that financial burden. While bulls and buffaloes were sold for meat, cows and oxen were freed in the jungles and neighboring settlements.

When India’s Uttar Pradesh state government, led by Yogi Adityanath, prohibited the killing and transportation of cows in Chaitra, 2073BS, it further increased the number of stray cattle. Before that, cattle from the remote areas of Kailali and Kanchanpur used to be taken to India.

Aiming to solve the problem, the community forest users’ groups began constructing Kanji Houses, to give shelter to stray cattle. But due to a lack of fodder and treatment at those set-ups, they couldn’t emerge as the permanent solution.

As time wore on, it became such a huge problem that political parties included controlling stray cattle as one of their main agendas for the local government elections in Asar, 2074BS. Local government with new leaderships then started constructing Gaushalas, animal shelters, rapidly.

Infrastructures were built; stray cattle were brought to them and shepherds hired to take care of them. The cattle were well-fed in the beginning. But gradually, hay and grass became scarce and the community forests were banned for grazing. As a result, committees constituted to run the Gaushalas began to dissolve. Stray cattle came back on the roads. And the infrastructures were left unused.

Irregularities in name of Gaushalas

Kanchanpur’s Bhimdatta Municipality constructed a Gaushala at Bagphanta in ward 19 at the cost of Rs4.8 million. An 8-bigha land from 8 farmers was leased for five years to construct the Gaushala in 2075BS. The ‘Jhapa Namuna Agriculture Organic Firm’, based in Bhimdatta-19, was contracted to run the Gaushala, built through the users’ committee.

The firm agreed to pay Rs1,11,111 to the municipality annually for running the facility. But four months after the contract, the firm’s proprietor Janga Bahadur BK went out of contact. With the contractor on the run, the infrastructure’s future became uncertain. The cattle returned to the streets once again. “The contract was scrapped,” says Hari Dhami, information officer at the municipality. “We issued notices seeking a new contractor but nobody came forward. The Gaushala couldn’t fulfil its stated purpose.”

Meanwhile, the municipality kept on paying the rent for the leased land, an annual Rs 160,000, for five years. After five years, the remains of the infrastructure were transferred

to the premises of Siddha Baijanath Tribeni Dham premises. The newly set up Gaushala at the Dham premises currently houses five cows.

Likewise, three Gaushalas at Janaki Rural Municipality in Kailali remain unused. In fiscal year 2076/77, a Gaushala was constructed at Manuwathada in Janaki-9 at the cost of Rs1 million. The Gaushala, built on the banks of Jarahi river, ran for a year. But the floods in 2078BS caused the river’s course to encircle the structure, rendering it unused, according to ward chair Khagendra Bhandari.

Two other Gaushalas in ward 3 and 6 of the rural municipality didn’t come into use. Between fiscal year 2076/77 and 2079/80, the rural municipality spent Rs3 million 370 thousand on Gaushala construction but none of them remain in use today, according to Santaram Kathariya, information officer of the rural municipality.

Likewise, the Gaushala built at Krishnapur Municipality-2 in Kanchanpur also remains unused, one year after it came into operation. The facility, built at the cost of Rs1 million, was closed after the management committee tasked with managing it didn’t pay attention to its smooth operation. Lokraj Bhatta, chair of the stray cattle control and management committee, says that he was left alone in the committee after other members quit. “I couldn’t run it single-handedly; hence it was close,” he said.

Financial difficulties

As many as 78 Gaushalas have been constructed in Kailali and Kanchanpur so far. Of them, 18 have already shut down, while 60 are still running, 32 of them with a very few cattle. 28 of them are running well.

Of the 51 Gaushalas in Kailali, 33 are no longer in operation. As many as 18 were built in Ghodaghodi alone, of which only two are in operation.

Most of the Gaushalas, built through grants from the local government and provincial government, have shut down due to a lack of income.

“It is imperative that the Gaushalas should produce milk and compost manure to become self-sustainable,” said Hem Bahadur Bista, a resident of Ghodasuwa in Dhangadhi. “There is growing tendency of putting cattle in Gaushala till local government provides fund and freeing them when the funding stops,” he added.

Tirtharaj Awasthi, a veterinarian at Seti technical school in Doti, says that if students from veterinary schools were sent to Gaushalas for practical learning, the facilities would be improved. There are 15 veterinary schools in Sudurpaschim alone, he says. “Currently, students are visiting private firms for practical learning,” he said. “If Gaushalas were well-managed, our students could go there instead.”

Meanwhile, some Gaushala operators are making good earnings. One of them is one based at Chatakpur in Dhangadhi Sub-metropolis-3. This facility, established in 2074BS, houses 143 cattle currently. Of them, 27 are local cows that produce as much as 32 liters of milk every day, according to Reeta Awasthi, manager of the cow conservation service committee.

The Gaushala is currently earning over Rs86,000 monthly through milk sales, Awasthi said. “We are also producing organic fertilizers,” she added. “We earn monthly Rs 30,000 from that.” While Rs75,000 is spent on paying salaries to officials supervising the cattle, the rest is spent on purchasing fodder.

Likewise, the Gaushala based at Urdipur in Tikapur-5 has been earning up to Rs600,000 yearly by managing stray cattle. This Gaushala currently houses 885 cattle. The facility makes income through milk sales and religious functions, according to the operating committee’s chair Lok Bahadur Budhachhetri. “We don’t sell fertilizer but exchange them with cattle fodder,” he said. “Milk is our main source of income.”

A Rs150 million investment

Local and provincial governments have so far spent about Rs150 million to manage stray cattle in Kailali and Kanchanpur.

Tikapur Municipality has alone spent Rs6.2 million in management of stray cattle since 2074BS; this fiscal year, it disbursed Rs1.5 million for the cause.

Likewise, Godawari Municipality has spent over Rs4.9 million in building infrastructure to manage stray cattle; this fiscal year, it disbursed Rs600,000 for Gaushala. Meanwhile, Gauriganga Municipality has spent over Rs1.63 million. Ghodaghodi has spent Rs10.5 million while Janaki Municipality has spent Rs5.87 million; it has disbursed Rs500,000 this fiscal year for the cause.

Similarly, Joshipur Rural Municipality has spent over Rs2.16 million and has disbursed Rs400,000 this fiscal year. Kanchanpur’s Laljhadi Rural Municipality has spent Rs5.55 million while Krishnapur Municipality has spent Rs10.7 million.

Under the provincial government, the Veterinary Hospital and Livestock Expert Centre Kanchanpur spent Rs1.5 million in 2078/79BS and Rs13.6 million in 2080/81BS to construct infrastructure alone.

Meanwhile, Dhangadhi Municipality has spent Rs26.3 million so far to construct the infrastructure for stray cattle management. The Veterinary Hospital and Livestock Expert Centre Kailali spent about Rs8.8 million in 2081/82BS in infrastructure construction. Likewise, the provincial livestock directorate Dipayal spent about Rs6 million in infrastructure construction for stray cattle management in 2081/82BS.

Corruption allegations

A study report by Veterinary Hospital and Livestock Service Expert Centre shows that despite massive investment, the effort to manage stray cattle in Kailali and Kanchanpur hasn’t been effective.

The report of the study, conducted under the leadership of then senior livestock development director Dr Hemraj Awasthi, had recommended measures to manage stray cattle sustainably. They included making the Gaushalas financially independent, bringing more Gaushalas into operation and increasing productivity, among others.

The report has also suggested producing not only milk and organic fertilizer but also organic pesticide and other agriculture essentials. Further, it has suggested a training be run to produce organic fertilizer, pesticide and incense sticks, among other things, through the ministry of land, agriculture and cooperatives.

Pusparaj Joshi, a journalist based in Dhangadhi, says that despite millions of spending by the local and province government to manage stray cattle, the problem has not budged. Joshi adds that irregularities and cases of corruption have been uncovered in stray cattle management in the district. “Statistics of stray cattle have been fabricated, while there’s been nepotism in granting contract,” Joshi said. “Likewise, receipts of fodder for the cattle are also inflated. Nobody has paid attention to the corruption committed in the name of stray cattle.”

Likewise, Hari Regmi, coordinator of National Consumers’ Forum Sudurpaschim, says that despite massive investment, the number of stray cattle in the roads has not decreased.

Meanwhile, the Sudurpaschim Province Policy and Planning Commission has claimed it would introduce a plan to make stray cattle “the basis of economic prosperity”. Nripa Bahadur Sunar, member of the commission, said that his office will introduce a scheme next fiscal year to improve the breed of stray cattle and increase milk production. “The plan aims to make Sudurpaschim independent in dairy products,” Sunar said.

Shankar Sah, secretary at the provincial ministry of land management, agriculture and cooperatives, also says measures will be introduced to construct model Gaushalas, launch grass-farming in fallow land, and generate income from Gaushalas.

But the reality is local residents and farmers are still suffering from stray cattle, said Lakshi Ram Acharya, a local politician. “This means the budget was not utilized,” he said. “A committee should be formed and this should be investigated.”

Biogas plant in limbo

In Kailali’s Tikapur, a biogas plant of 200 cubic meter capacity that made use of compost manure from the Gaushalas has remained unused for the past nine months. The plant was constructed at the cost of Rs16 million of the provincial government’s investment. The plant would distribute gas to 55 households for four hours daily.

Budhachhetri, the livestock management committee chair, says that the plant has been shut down despite the Gaushalas producing enough manure for its operation.

According to him, the Nepal Electricity Authority has disconnected power supply to the plant since January last year after the municipality didn’t pay dues worth Rs14,646. The biogas plant needs electricity to operate various machines.

Ram Prasad Adhikari, officer at Electricity Distribution Centre Tikapur, said that the fare has now reached Rs25,172, with added fines.

Chair Budhachhetri, meanwhile, says that they have requested the municipality to hand over the gas plant to the community livestock management and promotion committee. “But neither the municipality run it nor does it hand it over to us,” he said.

Buddhachhetri further says that if operated well, the biogas plant would generate good income and help manage the Gaushala even better. With the closure of the biogas plant, local residents have switched to LP gas to cook food.

Local residents lament the closure of the biogas plant.

“Biogas was very useful to us,” said Hari Bahadur Rawal, a local resident. “The plant would use not only cow dung but also biodegradable waste and agriculture residues. It had hence helped us keep the locality clean as well.”

More Investigative Stories

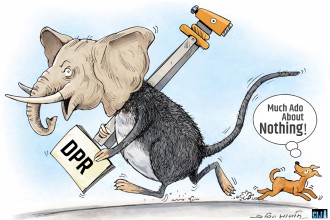

Nepal’s local governments have spent Rs1.5 billion in DPRs. Has it all gone to waste?

Many detailed project reports (DPRs) are neither on record nor have the proposed projects taken off. CIJ Nepal investigates what...

Pokhariya Municipality: The local government that has become the hotbed of organised corruption

The local government has witnessed illicit transfer and appointment of hundreds of officials. Many say they had paid for the...

Comment Here