Investigative Stories

It’s 4:30 in the morning. From the mosque’s minaret, the call to prayer echoes: “Allahu Akbar, Allahu Akbar.” “Babu, wake up quickly, you have to go to the madrasa,” -ten-year-old Arfa Khatun, who went to bed late last night, is awakened at the edge of her bed by her mother. Still sleepy, Arfa responds, “Yes, Ammi!” and after a while, she goes to perform ablution (wudu).

At Gausiya Taleemul Quran Madrasa, the Maulvi (teacher) starts teaching the children by 6 am, following the Fajr (dawn) prayer. Arfa sits among the students and begins memorizing the Quran. As the clock strikes 9, she rushes home. Within an hour, after eating and changing into her school uniform, she is back at the Public English Boarding School, standing for prayers.

By the time she gets home from school at 4 pm, Arfa Khatun from Janakpurdham-20, Rupetha is already exhausted. She still has the “homework” from both school and madrasa to complete. “I only go to bed around 10 pm after finishing both sets of homework,” she says.

Arfa’s friend, 13-year-old Ramun Khatun, follows a similar routine; religious education in the morning, modern education in the afternoon. She says, “When I am very tired, sometimes I skip a madrasa class, and sometimes a school class.”

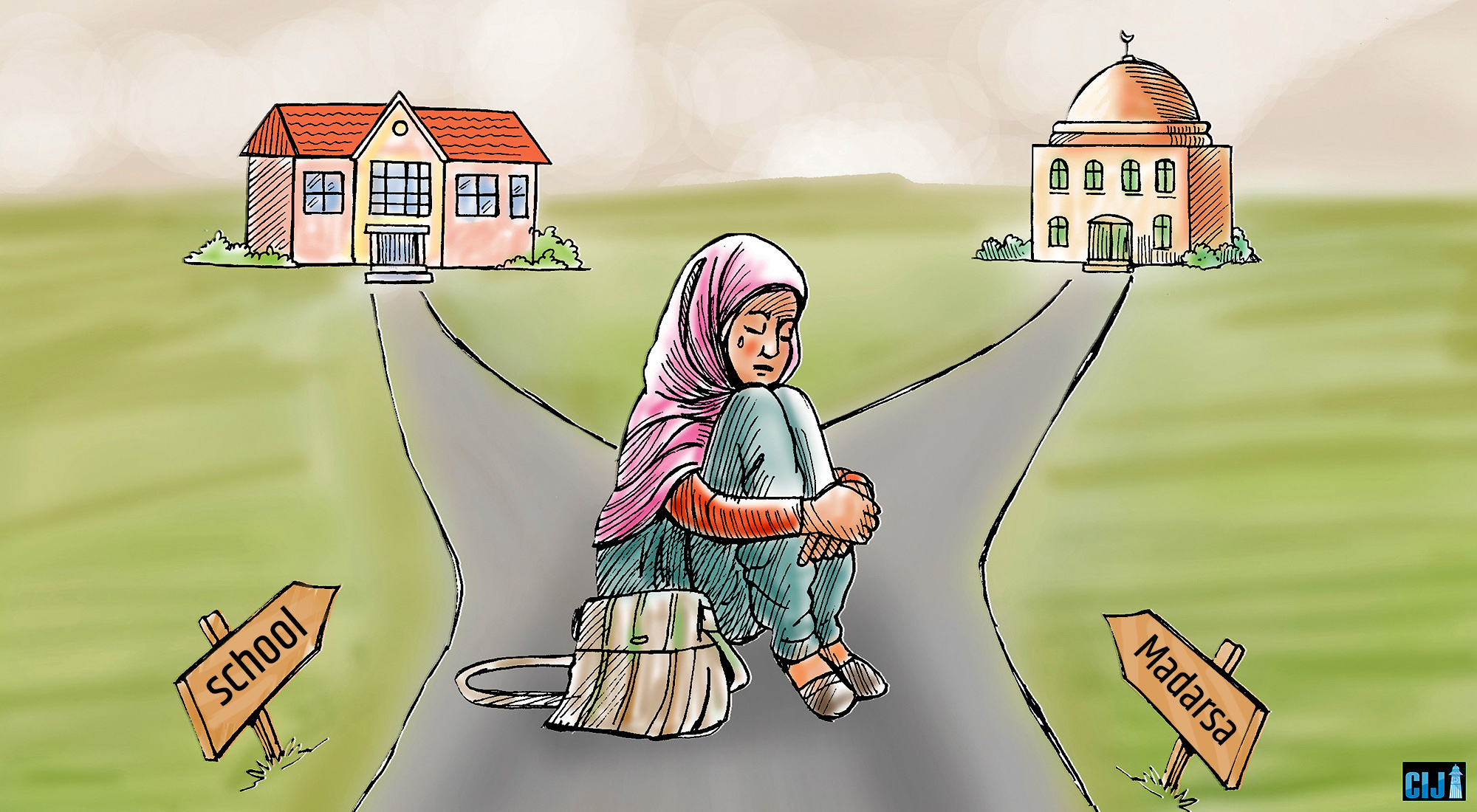

The burden of managing two kinds of education is becoming increasingly difficult for these children. Unlike other children, they don’t get the chance to play, enjoy holidays, or have fun. When schools are on break, the madrasa is still in session, and when the madrasa is on holiday, school continues. When this heavy load becomes too much, children in the Muslim community are dropping out of studies altogether.

Zoya Azmin, 14, studying in class 9 at Gyankup Secondary School in Janakpurdham, attended both school and madrasa until class 6. She recalls, “Attending both types of schools was a real burden. Watching other children of my age enjoying themselves made me feel left out, so I left the madrasa and now attend only school.”

Similarly, 16-year-old Sagufa from Hansapur Municipality-4 in Dhanusha left school while studying in class 10 at Shri Sarvodaya Secondary School, Paudeshwar. “My parents said I had already learned enough Nepali, Maths, and English, and it was time to focus on the Quran and Hadith, so I left school,” she explains. “If all types of education were offered in the same school, I wouldn’t have had to quit.”

Across the country, many children like Arfa and Sagufa are either forced to leave formal education or struggle under the burden of managing two parallel schooling systems.

Mohammad Asgar Ali, a Muslim community leader in Janakpurdham-5, believes that children should not be deprived of modern education or burdened with two schools. He says, “Once children reach a certain level in modern education, those interested can also pursue religious studies. But in our society, this mindset and practice haven’t developed yet.”

According to Ali, the problem is even greater among the underprivileged sections of the Muslim community. He identifies two main reasons why parents send their children to madrasa.

First, they want their children to lead a life according to Sharia (Islamic religious rules).

Second, some parents want their children to focus on study Islamic scriptures and pursue religious work, believing that sharing knowledge of the Quran and Hadith brings the spiritual reward (sawab) even after death. However, Ali points out, “Islam teaches that knowledge which does not help one earn a livelihood is not considered true knowledge.”

Confused Community and Indifferent Government

The word madrasa, derived from Arabic, means a place of learning or an educational institution. In the early days of Islamic civilization, madrasas were known as centers for teaching religious texts such as the Quran and Hadith, along with Arabic and Persian languages. Gradually, madrasas began offering not only religious education (Deeni) but also modern (Duniyavi) education.

In Morocco, in 859 A.D, the Al-Qarawiyyin Madrasa was established under the leadership of Fatima al-Fihri. Over time, it evolved into a full-fledged university. UNESCO and the Guinness World Records, recognized it as the world’s oldest university that has been in continuous operation since its founding. While it initially focused on religious and linguistic studies, it now offers education in Arabic literature, law, economics, management, and other fields.

However, not all madrasas have been able to achieve such improvements. Since most are run by socially and economically marginalized communities, many madrasas in Nepal are unable to provide proper Ilm (knowledge). They also lack the necessary resources and infrastructure.

Muslims make up about 5.09% of Nepal’s total population. While the country’s overall literacy rate is 76%, the literacy rate among the Muslim community is only 61%. Female literacy is even lower in Muslim community, with just 54% compared to the national female literacy rate of 69.4%.

According to the Education and Human Resource Development Center, there are currently 1,207 registered madrasas across Nepal. Of these, 7 offer education up to grade 12, 20 up to grade 10, 104 up to grade 8, and 1,076 up to grades 1 to 5. These figures account only for madrasas registered with government authorities-currently local municipalities, previously District Education Offices. The number of unregistered madrasas is even higher.

The Muslim Commission estimates that Nepal has around 3,000 madrasas in total, ranging from pre-primary to college level, with approximately 200,000 students enrolled in them.

There are three main types of madrasas in Nepal. First, those that implement the government curriculum along with religious studies and are officially linked to the state education system. These madrasas are registered with government authorities and operate under official supervision. Students from these madrasas face no barriers to pursuing higher education or entering government service.

The second type consists madrasas that are not registered with government authorities. They focus primarily on religious and cultural subjects, and partially implement the government curriculum. Typically larger in size, these madrasas often have better physical infrastructure than the first type, and in some cases, offer their own curriculum up to the undergraduate level. Their main objective is to produce skilled religious personnel.

Examples include Hanfia Tul Gausiya in Janakpurdham, Jamia Serajul Uloom in Krishnanagar, Kapilvastu, and Darul Uloom Nurul Islam in Jalpapur, Sunsari, which follow curricula adopted by various madrasas in India. Certificates issued by these madrasas are not recognized by other universities or by the government in Nepal.

Third, small madrasas that are not registered anywhere and provide only religious education. Certificates from these madrasas are also not recognized by the government.

These madrasas fear that registering with government authorities might lead to interference in their curriculum, dress code, and prayer practices. Some madrasas exist solely to educate female students. These are called Banat, and most of them operate without registration.

Madrasas follow the Islamic calendar. Their weekly holiday is on Friday, and they observe breaks during festivals like Ramadan while continuing religious education.

“That’s why there are concerns that registering madrasas with the government will increase the interference,” says Mufti Usman Barqati, principal of Faizane Madina Madrasa in Janakpurdham-16. “If the government formulates a clear policy that respects the traditions and originality of madrasas, this problem would not exist.”

Bachcha Kawadi, chairman of Hanfia Tul Gausiya Madrasa Management Committee in Janakpur shares that registering the madrasa with government authorities would place it under local government regulation and control, but it would not bring any support. Hence, it remains unregistered.

“If we register with government authorities, we would be required to run classes in Nepali, Math, English, and other subjects,” he says. “But the government does not provide financial assistance to conduct all these classes. That’s why we currently rely on the donations collected from the community to run the madrasa.”

Giving an example of how interference increases with registration, Muslim leader Mojim Rain from Mahottari recalls, “A madrasa in Matihani was taken over and converted into a community school.”

He explains that the Faizul Guruwa Madrasa, established around 40 years ago in Matihani-2, Bardaha, was registered with the District Education Office. A few years later, under the pretext of securing government grants and adding teaching positions, the madrasa’s name was changed to Sri Faizul Guruwa Primary School.

“Since the madrasa was transformed into a community school, contrary to its purpose and tradition, many madrasas now do not want to register,” Rain adds.

Widespread madrasas, questionable quality

On one hand, many madrasas lack quality education, have weak physical infrastructure, and operate without registration, making it difficult for students to pursue higher education and secure employment.

On the other hand, in densely populated Muslim settlements, some mosques provide religious education only up to the pre-primary level. These types of madrasas often maintain no formal records.

In Rupetha, Janakpurdham-20, a Muslim settlement of about 400 households have six madrasas. Janakpurdham-16 has three madrasas and two Banats. In Hansapur Municipality-4, Dhanusha, there are three madrasas, only two of which are registered. In Janakpurdham-6, two madrasas exist just 200 meters apart.

Across the country, in Muslim settlements, there are mosques and the madrasas they run. However, most of them lack proper infrastructure and quality education.

Jasim Shesh, chairman of the Gausiya Taleemul Quran Madrasa Management Committee, explains that 70 households contribute a monthly donation of Rs. 250 to cover the Maulvi’s salary. “Managing the salary is a struggle, so there hasn’t been much focus on improving quality of education”, he adds.

A 2078 study by the Muslim Commission in Morang, Sunsari, Rautahat, Parsa, Dang, and Syangja found that, out of 236 madrasas, only 129 had permanent buildings. In other words, 45.34% of madrasas operate in temporary huts. Additionally, 76% lack toilets, and 86% do not have access to drinking water.

Most of these madrasas, attended primarily by underprivileged and orphaned children, are funded through local donations and zakat. Madrasas established throughout settlements are therefore unorganized, and their educational standards are poor.

Shesh says, “In my ward, there are six madrasas and maktabs. If the government were to merged them and established a single organized madrasa in each ward, both religious and modern education could be offered in one place. It would be possible to improve both education and infrastructure.”

Educationist Bidyanath Koirala also suggests merging the scattered madrasas at the ward or municipal level to establish organized madrasas. “Madrasa education should not be kept outside the mainstream education system”, he says. “Students in madrasas are citizens of this country too. The state must invest in their education, and there should be a single authority responsible for monitoring.”

He emphasized that just as gaps exist between community and private schools, it is necessary to bridge the divide between community schools and madrasas. Maulana Faruq Barqati, central vice-chair of Ulma Council Nepal, believes that the scattered madrasas in settlements need to be organized.

He suggests merging registered madrasas into a single madrasa per ward and making it mandatory for unregistered madrasas to operate according to government-prescribed standards, similar to private schools. He emphasizes, “Only then can there be uniformity in the madrasa curriculum, and the educational condition of Muslim children can improve.”

Countries like India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Indonesia also have two types of madrasas. The first category follows curricula determined and monitored by the government or government-recognized institutions; for example, various Madrasa Boards in Indian states or the Madrasa Education Board in Bangladesh.

The second category consists of independent madrasas. These madrasas develop their own curricula and textbooks, with the primary goal of producing religious personnel.

Educationist Koirala emphasizes that in Nepal, instead of following the models of India or Bangladesh, a policy suitable for Nepal’s multi-religious and multi-cultural society should be formulated.

One madrasa, two streams of learning

At the Nepali Jama Masjid in Bagbazar, Kathmandu, an Islamic madrasa is in operation. Registered under a private trust, the madrasa currently provides education from nursery up to class 10.

According to the madrasa principal, Firoz Khan, there are two types of education offered. One follows the curriculum prescribed by the Government of Nepal i.e. modern education, and the other is developed by the madrasa itself i.e. Deeni (religious education).

For students taking religious education, the madrasa also teaches Nepali, Maths, English, and Computer subjects at the initial (Nazra) level. However, once they reach the Hifz level (memorization of the Quran), only religious subjects are taught. According to Khan, 38 students are currently enrolled in religious education, while 245 students follow the government curriculum. Of the 19 teachers, 12 are women, and 7 are from the Hindu community.

The Sulfia Tul Hanfia Madrasa in Janakpurdham-6 also offers both religious and modern curricula. The madrasa, registered up to class 5, has around 250 students enrolled.

Mokim Rain, vice-chair of the madrasa management committee, says, “We teach textbooks approved by the government for private schools. For religious books, we rely on the curriculum from Indian madrasas.”

According to him, although the Janakpurdham Sub-Metropolitan City provides a small annual grant to the madrasa, it does not cover expenses for students’ snacks, books, or uniforms. “The government gives only two to three lakh rupees annually, without funding for teachers or textbooks. In such a situation, how can we manage teachers’ salaries and other expenses?” Rain asks.

He adds that the madrasa’s expenses are met through monthly donations from the community, contributions from families during weddings and other celebrations, as well as zakat and khairat (religious charitable funds).

Unresponsive provincial authority

Schedule 9 of the Constitution places education under the shared authority of the three levels of government, while Schedule 6 assigns higher education exclusively to the provincial government.

According to Nepal Government’s Functional Expansion Report, the provincial governments are responsible for developing curricula and textbooks for school and technical education, managing teachers’ professional development, and overseeing secondary-level examinations. Therefore, it is also the duty of the provincial government to provide citizens with access to quality education. However, in practice, provincial governments have not fulfilled this responsibility.

Attending both types of schools was a real burden. Seeing other children of my age enjoying themselves made me feel left out. That’s why I left the madrasa and now only attend school.

- Zoya Azmin, Grade 9, Gyankup Secondary School, Janakpurdham

About 80% of Nepal’s Muslim population resides in Madhesh Province, where Muslims make up 12% of the total population. Yet, the provincial government appears indifferent toward madrasas, which are often the first place where children from economically disadvantaged Muslim families access education.

Mahendra Mahato, director of the Education Development Directorate of Madhesh Province, says, “There is no program to support the quality of education in madrasas or any other religious and traditional learning institutions.”

Madhesh Province’s Education Policy (2081) mentions integrating religious institutions including madrasas, gurukuls, viharas, and gumbas into the mainstream education system and providing support to local authorities for their implementation and regulation.

However, this policy remains largely on paper. Mahato says, “Although the government’s policy mentions improving the quality of education in religious institutions, there has been no budget allocation for it.”

On 14 Bhadra 2075, the first cabinet of Madhesh Province’s Chief Minister Mohammad Lalbabu Raut introduced a Bill in the provincial assembly to establish a Madrasa Education Board. After facing opposition, the bill was sent to the Women, Children, and Social Justice Committee to reach a consensus.

Jayanul Rain, then-chair of the committee, says, “We held repeated meetings to build consensus on the Bill and even consulted experts. But instead of actively participating, both supporters and opponents remained silent during discussions. The bill could not move forward.”

In contrast, Lumbini Province has formed a Provincial Madrasa Education Management Coordination Committee to mainstream madrasa education. oversees everything from monitoring to managing madrasas. Operating under the Ministry of Education and Social Development of Lumbini Province, the committee oversees everything from monitoring to managing madrasas. It has initiated efforts to bring madrasas across the province into the mainstream education system.

The committee is also responsible for advising local governments on issues such as opening, relocating, and merging madrasas, as well as collaborating with various agencies and organizations to ensure quality education in these institutions.

The committee has been tasked to encourage unregistered madrasas to obtain formal registration. According to former vice-chair Masahud Khan, this has led to increased number of registered madrasas in Lumbini Province. “There has been improvement after the committee was established. Although small, the grants provided to madrasas have increased, children have begun receiving facilities such as mid-day meals and scholarships similar to those provided in community schools,” he added.

However, he shared that due to limited authority and budget, the committee has not been able to work as effectively as expected.

‘Useless certificates’

Madrasa education is divided into three levels: Maktab, Alimiyat, and Fazilat. Maktab is considered equivalent to the primary level, Alimiyat to the secondary level, and Fazilat to the bachelor’s level.

No matter how much students study in madrasas, if the educational certificates are not recognised, they have no basis to claim employment. Therefore, the government must take immediate interest in this issue.

- Najrul Hasan, President, The Islamic Association Nepal

However, the certificates issued by madrasas that follow their own curriculum are not recognized by other educational institutions or the government. Without formal recognition, students are unable to pursue higher education or secure employment. Except for those who choose to engage in religious work, the certificates become practically useless for young people who spend their most productive years studying in madrasas.

19-year-old Aisa Khatun from Aurahi Municipality-1 in Mahottari has completed Alimiyat. However, because her certificate is not recognized by the government, she is now studying in Grade 8 at the local secondary school nearby.

Aisa said that despite having a good foundation in Nepali, Mathematics, and English, she would be ineligible to pursue higher education or get a job.

Former state minister and activist Zakir Hussain accuses the government of neglecting madrasa education reform. “It is the government’s responsibility to reform madrasas, because a large group of Nepali citizens study there. But the government doesn’t seem to care about its own citizens.”

The Islamic Association Nepal had already called a nationwide gathering of madrasa operators in 2073, urging the government to formulate a separate act to systematize madrasa education. The association’s president, Najrul Hasan, says, “No matter how much students study in madrasas, if the educational certificates are not recognized, they have no basis to claim employment. Therefore, the government must take immediate interest in this issue.”

Half-hearted government measures

According to former deputy mayor of Janakpurdham and a prominent Muslim community leader, Mohammad Asgar Ali, the Government of Nepal had recognized primary-level madrasa education from 2012 BS to 2028 BS. However, after the new education policy came into effect in 2028 BS, the recognition was revoked.

In 2051 BS, the Manmohan Adhikari-led government formed a Madrasa Study Taskforce. But its recommendations never moved beyond paperwork.

Again in 2066 BS, the government formed the Madrasa Education Council to identify policy gaps and provide suggestions. Due to weak procedures and lack of budget, the council was unable to deliver the expected results. Instead of strengthening and institutionalizing it, the government dissolved the council altogether in 2079 BS.

Mirza Arshad Beg, spokesperson and member of the Muslim Commission, says that since its first annual report in 2075/76 BS, the commission has been recommending the government to develop a standardized curriculum for madrasas, integrate madrasa education into the mainstream, and formulate a Madrasa Education Act.

In 2078, the commission conducted a study on madrasa education and its future transformation in six districts and submitted the report to the government. Copies were also handed over to the chiefs of all seven provinces. However, the report was left to gather dust in drawers.

Muslim leaders say that even the School Education Bill presented in the House of Representatives in 2080 BS failed to address the core concerns of madrasa education. They had provided recommendations for amendments to Amar Bahadur Thapa, then chairperson of the dissolved House's Education, Health, and Information Technology Committee.

Madrasa education activist and former state minister Zakir Hussain points out that while the bill mentions bringing traditional religious institutions such as madrasas, gurukuls, Gumbas, and Sanskrit schools into the mainstream, it remains silent on the actual process for doing so. He explained, “The Bill does not address issues like physical infrastructure, teacher appointments, or training for religious and traditional schools. It says government curriculum should be implemented in these schools, but expects the community itself to run them.”

Because of the provisions in the Bill, some madrasas may even lose the grants and support they have been receiving from local governments, he believes. Committee chair Thapa says, “We may not have been able to revise the Bill exactly as proposed by Muslim community leaders, but its essence has been incorporated.”

Published in Naya patrika on 2 December 2025

More Investigative Stories

Pokhariya Municipality: The local government that has become the hotbed of organised corruption

The local government has witnessed illicit transfer and appointment of hundreds of officials. Many say they had paid for the...

Hotter Himalaya melts glaciers

Villages in Manang live directly below a glacial lake that is in danger of bursting

Comment Here