Investigative Stories

Kathmandu – Laxmi Pariyar from Chandannath Municipality, Ward No. 4, Jumla, vividly remembers the moment she received her first appointment. "As an unemployed person, getting a government job felt like conquering the world," she says. Pariyar was appointed to the position of Kharidar (non-gazetted officer) in her second attempt in 2015. She is currently working at Chandannath Municipality.

The story of Pran Mehta, the administrative head of Paterwa Sugauli Rural Municipality in Parsa, is even more intriguing. Before he moved to Birgunj in 2012 to study in the 11th grade, he was unaware that there was an institution called the Public Service Commission that conducted exams for entry into the civil service. Mehta says, "As far as I know, no one in my entire community, let alone my family, had ever been in government service."

While pursuing higher education, Mehta also began preparing for the Public Service Commission exams. In 2015, he was selected for the position of Nayab Subba (non-gazetted first-class officer), with his first posting in Mustang. Later, in 2017, he qualified for an officer-level position. He is now serving as the administrative head of Paterwa Sugauli Rural Municipality.

The Fruits of Inclusivity

The Public Service Commission, established 73 years ago, only began its inclusive recruitment process from the fiscal year 2008/09. Since then, faces like Laxmi Pariyar and Pran Mehta have become more common in the civil service. Prior to this, individuals from marginalized communities, long left behind, would only enter the civil service as rare exceptions.

On August 8, 2007, the "Civil Service Act – 2049 B.S." was amended and implemented. The main objective of the amendment was to introduce a policy of positive discrimination, or reservation, to allow marginalized communities to enter government service. Because Nepal's civil service had long been dominated by certain castes and communities despite the country's ethnic diversity, a constitutional provision was established to ensure equal representation for all communities. The provisions introduced by the interim constitution were then continued in the 2015 Constitution.

The diverse faces now seen in government services, representing various ethnicities, are a direct result of the inclusivity measures. Fifteen years after its implementation, a total of 25,218 individuals have entered government service through the 45% reservation quota for the marginalized which includes women, Indigenous people, Madhesi, Dalits, people with disabilities, and those from marginalized regions. Additionally, since 2008/09, 36,537 individuals from these communities have joined government service through open competition, according to data from the Public Service Commission. At first glance, the inclusive system in government services seems to have made a significant positive impact.

However, despite government statistics showing adequate representation of marginalized communities in government services, some voices are now calling for an end to the quota system. Our investigations also reveal that the very groups for whom the system was created and for whom special constitutional provisions were made are still not sufficiently represented in government services. In other words, the representation of the most marginalized and disadvantaged communities in the civil service remains minimal.

Falling Through the Cracks

At first glance, a quick survey of the data published on the Public Service Commission's website, indicates that the number of employees selected by the commission aligns with the provisions of the inclusivity act. However, when analyzing the applications and exam records for entry into the civil service over the past seven years based on district, ethnicity, and language, it becomes clear that participation from the most marginalized communities has been minimal, with only a few exceptions. The representation of Madhesi Dalits, Muslims, and endangered communities in the exams conducted by the commission is barely 1 to 2 percent, far short of their population percentages.

Manoj Paswan, a social activist from Aurahi Municipality in Siraha, says that while the data may suggest that Madhesis, for example, have benefited from reservation, Madhesi Dalits, Muslims, and Madhesi women have not received adequate benefits. He states, "The situation of Madhesi Dalits is horrific; they haven't received any benefit from the quota system. The one or two percent who have been selected for service, have done so through their own efforts."

Paswan charges political parties of shirking their responsibility of uplifting the marginalized within the Madhesi community, who are suffering from poverty, illiteracy, and oppression. He says, "In particular, a large segment of the Madhesi Dalits are exploited by the upper class.” According to Paswan, political parties that campaign in the region during elections do not promise to build proper schools in the Madhesh. Instead, they propose plans for concrete roads and temples. Paswan points out that the lack of urgency from political parties regarding education in the Madhesh has prevented the Madhesi Dalit community from moving forward. Tharu rights activist and lawyer Geeta Chaudhary agrees that marginalized groups still lack access to education. She says, "There is a lack of awareness about what educational qualifications are required for which civil service exams. Without access to education in marginalized communities, it becomes impossible for them to reach that level."

The "Status of Inclusivity in Civil Service – A Study Report," jointly published in February 2024 by the National Women's Commission, Dalit Commission, Indigenous Nationalities Commission, Madhesi Commission, Tharu Commission, and Muslim Commission, has also highlighted the uneven implementation of the reservation system.

According to data from 2012, the representation of hill women in Nepal's civil service was 10.1%. By 2019, this had increased to 15.6%. Similarly, in 2012, the representation of Indigenous nationalities was 12.5%, and by 2019, it had increased to 14%, a growth of 1.5%. However, the representation of Newars, the Indigenous community from the capital, stands at 5.9%. The representation of the Dalit community was 1.7% in 2012, and increased to only 2.8% by 2019.

The same report indicates that the representation of Brahmins in the Madhesi region increased from 8.1% to 11.5%. But while the representation of Brahmin and Kshetri communities in Madhes has improved, the representation of other castes within the Madhesi community remains woeful. Among marginalized communities, the Muslim community had a representation of 0.5% in 2012, which only increased slightly to 0.7% by 2019.

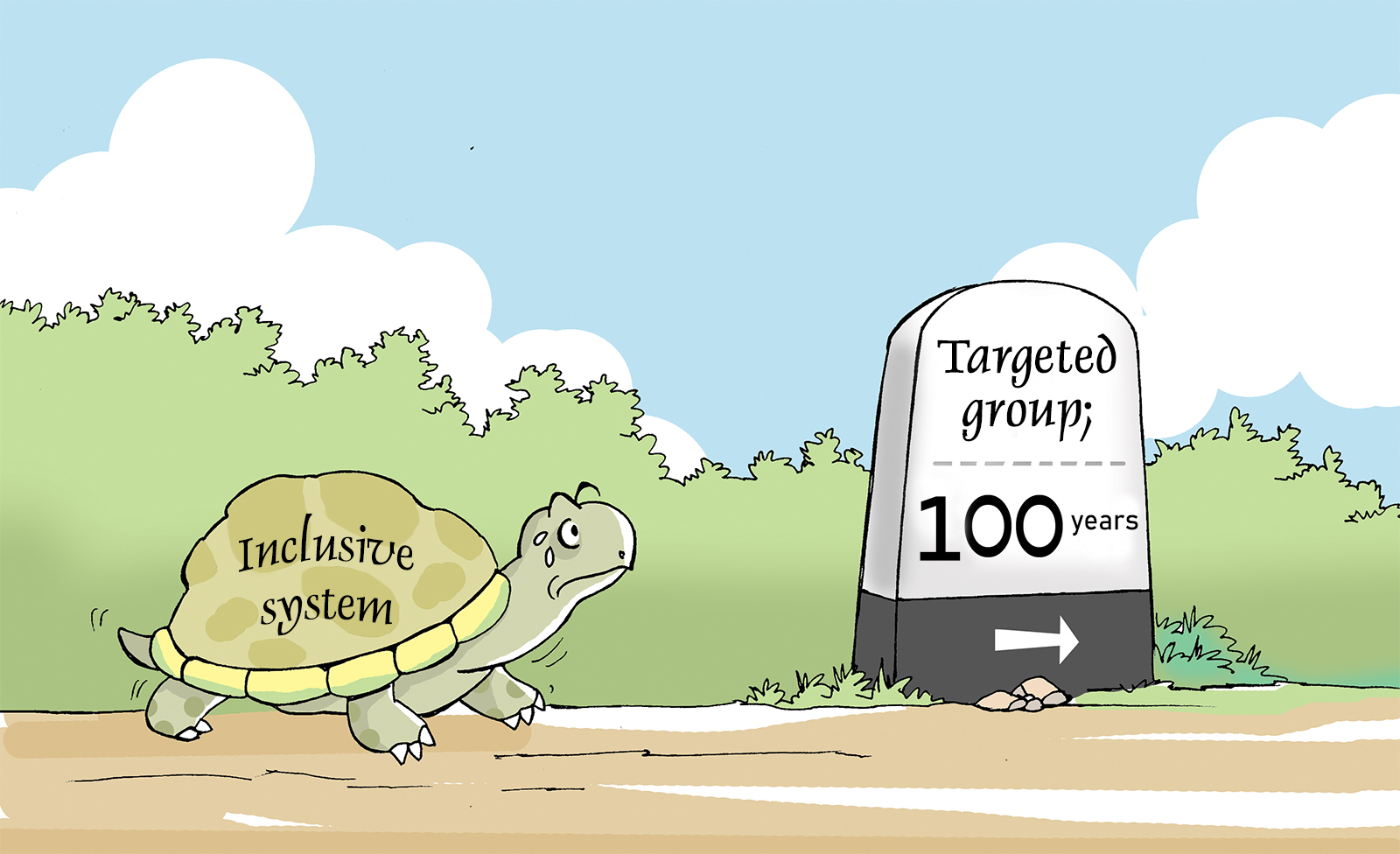

Since the implementation of inclusive policies, data on individuals entering government service through reservations reveals that proportional representation of the targeted groups remains insufficient. The report from the six aforementioned commissions suggests that achieving adequate representation at the current pace could take a century or more. According to the study, achieving the 50% proportional representation for women, based on their population, will take an additional 66.66 years. Similarly, the study estimates that proportional representation of Indigenous communities (35%) will require 166 years, while Dalits (13%) will need 82 years to reach proportional representation. The report asserts that it will take 175 years for the Muslim community to achieve proportional representation of 5%, based on their population.

In contrast, the National Inclusion Commission has argued that reservations will no longer be necessary after 2044 – in twenty years' time.

Dr. Man Bahadur BK, a former government official and a member of the study team, contends that despite Dalits making up 13% of the population nationwide, their participation in civil service has only increased by 1.1% over the past 16 years. Based on this data, he concludes that achieving proportional representation for Dalits would take more than half a century. He says, "If the situation remains the same, it will take a long time to increase their participation from 2% to 13%." The report also suggests that reservation will continue to be necessary until proportional representation is achieved based on population.

Marginalized Voices Absent in Leadership

While the increasing inclusivity in government services signals some progress, change is materializing at a glacial pace. Even though inclusive representation at the official level appears satisfactory, the situation in specialized categories of service remains discouraging.

According to the joint study report of the six commissions, by 2019, only four individuals from the Indigenous nationalities, one from the Dalit community, and two from the Muslim community reached specialized categories of government service. The Tharu community, for example, represents 6.6% of the country’s population but it only has a 3.64% presence among non-gazetted officers and 2.28% among gazetted officers in civil service.

Dr. BK, who is the only Dalit to have risen to the rank of secretary, states that despite the long history of the reservation system, it has failed to achieve the desired level of representation. While participation has increased in terms of numbers, he points out that marginalized groups still lack presence at decision-making levels. He says, "Even after all this time, the groups that have been the most marginalized have not been able to reach the upper echelons of governance."

Reform or Abolish?

The National Inclusion Commission's "Study Report on the Impact of Reservation in Existing Government Services (2079 B.S.)" analyzes the participation in government services post-inclusivity and indicates that the 45% participation envisioned by the constitution will be achieved before 2091 B.S. (2044) The report argues that after that, maintaining reservation beyond then would only limit the potential for individuals to advance through fair competition. In the case of the health sector, the report states that since the retirement period is two years longer than in civil service, the reservation system in health services will no longer be necessary after 2093 B.S (2046).

While the National Inclusion Commission’s latest report has naturally sparked discussions about the reservation system’s abolishment, Bishnu Maya Ojha, the executive chairperson of the commission, advocates for measured and thoughtful deliberation. "Our recommendations also need to be considered," she explains. "There was a lot of uproar claiming that the Commission advocated for abolishing inclusivity, but that is not true. We believe that the privileged and the children of affluent families should not be eligible for reservation. Those who truly need the benefits of reservation have yet to see meaningful gains and remain excluded. Unfortunately, the recommendations we provided were not properly highlighted."

Ojha claims that stakeholders have appreciated the commission's report and recommendations after thoroughly studying them. The National Inclusion Commission's report, submitted to the government on Magh 15, 2080 B.S., highlights that, as of 2079 B.S., 76 castes had no political representation in the Constituent Assembly, National Assembly, House of Representatives, Provincial Assemblies, and both federal and provincial executive bodies.

Another report published in 2078 B.S., titled “Impact of the Existing Reservation System in Government Services”, suggests that the reservation system should be temporary and phased out as soon as possible while also recommending improvements to the current framework. The report, for example, recommends implementing additional training and capacity-building programs for those who enter government service through the reservation system. It also advises against including reservation provisions in internal promotions and other career advancement opportunities. Furthermore, the commission suggests refining the reservation system to scientifically reach the most marginalized groups, eliminating the practice of individuals repeatedly benefiting from reservation quotas, and ensuring opportunities for those who have never had access to such benefits.

"We are not saying that reservation should be abolished right now, but that the current system should be reviewed so that those who deserve reservation can actually receive it," says Ojha. The commission has also prepared a list of 50 extremely marginalized groups and recommended their inclusion in government.

A way forward

Section 9 (110) of the Civil Service Act (Second Amendment – 2064) requires that the inclusivity system outlined in Subsection 970 of the Act be reviewed every 10 years. However, although mandated by the Act, the system has not been reviewed to date.

Uday Rana, who served as the Consul General of Nepal to Hong Kong, believes that allocating blanket quotas has not been effective. “If we look at the civil service, we allocated blanket quotas. We said 'women,' but we didn’t categorize within this broad group,” he says. “Moreover, how many times should an individual be allowed to benefit from reservations? For instance, someone born in a remote area is benefiting from the remote area quota. If that person has a minor visual impairment, they are also benefiting from the disability quota. If they belong to an ethnic group categorized as Indigenous, they are availing themselves of that quota too.”

When one person repeatedly benefits from the system, another is deprived, he says. However, he emphasizes that reservation should be maintained until proportional representation is fully achieved, even if it takes 30 more years.

Dr. BK also maintains that social justice and a change in the character of the state will only occur if proportional inclusion is applied in political appointments, the electoral system, government machinery, and the private sector as well.

Associate Professor at the Tribhuwan University Krishna Mabuhang Rai argues that the current 55% open and 45% inclusive competition should shift to favor more inclusivity. He highlights that while Nepal is a culturally diverse country, inclusivity in state mechanisms remains exceptionally low. He suggests that the quota for inclusivity should be increased, as the current 55-45 ratio was established without a scientific basis.

Former Chairperson of the Public Service Commission, Umesh Mainali, who has been advocating for reservations, believes that inclusivity has increased proportional participation in both the civil service and politics. However, he expresses doubt that the reservation system has reached the most marginalized sections of society, those who are truly at the bottom rung and for whom the system was designed.

"It is not possible to create sub-quotas within the reservation system. Therefore, it should be revised by introducing provisions such as eliminating reservations for individuals who have already reached a certain level, excluding the children of wealthy parents or those in high positions, and ensuring that no one benefits from the reservation system more than once," says Mainali.

Mainali acknowledges that reservations have somewhat increased the representation of women and Indigenous groups, but they have not yet reached decision-making levels. He also points out that significant disparities exist within large groups benefiting from reservations. "When we say 'women,' we have only considered women as a whole, and it is evident that only Khas-Arya women have significantly progressed within the system," he explains. "In the Madhesi quota, only the upper castes such as Thakur, Yadav, and Jha have benefited. Similarly, among Indigenous groups, representation is limited to Limbu, Gurung, Tamang, and Magar communities. We failed to account for the diversity within these groups," he adds.

He explains that the current situation has arisen because the reservation system was not reviewed within ten years as stipulated by the law. He believes that after reviewing the law, the inclusive system can be better aligned to its original goal. "The straightforward formula is to correct it, not abolish it," he says. "This is based on the principle of social justice. Social justice cannot be overlooked at this time."

More Investigative Stories

Hotter Himalaya melts glaciers

Villages in Manang live directly below a glacial lake that is in danger of bursting

Stray cattle continue to haunt Kailali and Kanchanpur streets despite massive investment to manage them

Streets and settlements in Kailali and Kanchanpur have been teeming with stray cattle for years, destroying crops and causing road...

Comment Here