Investigative Stories

Smriti, 33, worked at a hotel in Thamel when she met Man Maya Ghale. Having lived in poverty, Smriti was drawn in by Ghale’s promise of marriage to a Chinese man, a union that, according to Ghale, would "eliminate all her sorrows" and allow her to "live like a queen." It didn’t take much to convince Smriti. A meeting between the Chinese man and Smriti's family was arranged, and soon after, the two were married. Smriti barely knew the man and did not speak a word of Chinese.

With the marriage registered at the Kathmandu District Court, Smriti, who had studied up to the 10th grade, obtained a marriage certificate. Within three weeks, she flew to China with her new husband. Before they left, Ghale handed 70,000 rupees to Smriti’s family — as a gift from the groom.

After arriving in China, Smriti’s contact with her family in Nepal gradually diminished. About a year later, she gave birth to a baby boy. That’s when things took a darker turn. Her husband banned her from communicating with her family and began physically abusing her.

Now, her son is five years old. Her husband has separated from her and moved to a different location, leaving her in isolation. “I’ve been thrown out of the house. My husband lives separately. I can only see him when he calls for me. If he doesn’t, I have to stay away,” she said during a brief conversation. “I can’t work to support myself here. I can only eat if my husband provides for me. There are 15 to 20 other women like me who came here 15 or 16 years ago but still don’t have citizenship. The Chinese just want children, not mothers. We want to return to Nepal by any means. We’re trapped. The government must take steps to bring us back!”

Smriti’s family has lodged complaints with Nepal’s Human Trafficking Bureau, the National Human Rights Commission, and the Nepali Consulate in China. But since Smriti is married to a Chinese citizen and has a child with him, legal complications have arisen, making it difficult to bring both mother and child back to Nepal.

The woman at the heart of this trafficking scheme, Man Maya Ghale, is now facing charges of human trafficking at the Kathmandu District Court. Ghale herself is married to a Chinese citizen. Police investigations revealed she had orchestrated multiple marriages between Nepali women and Chinese men.

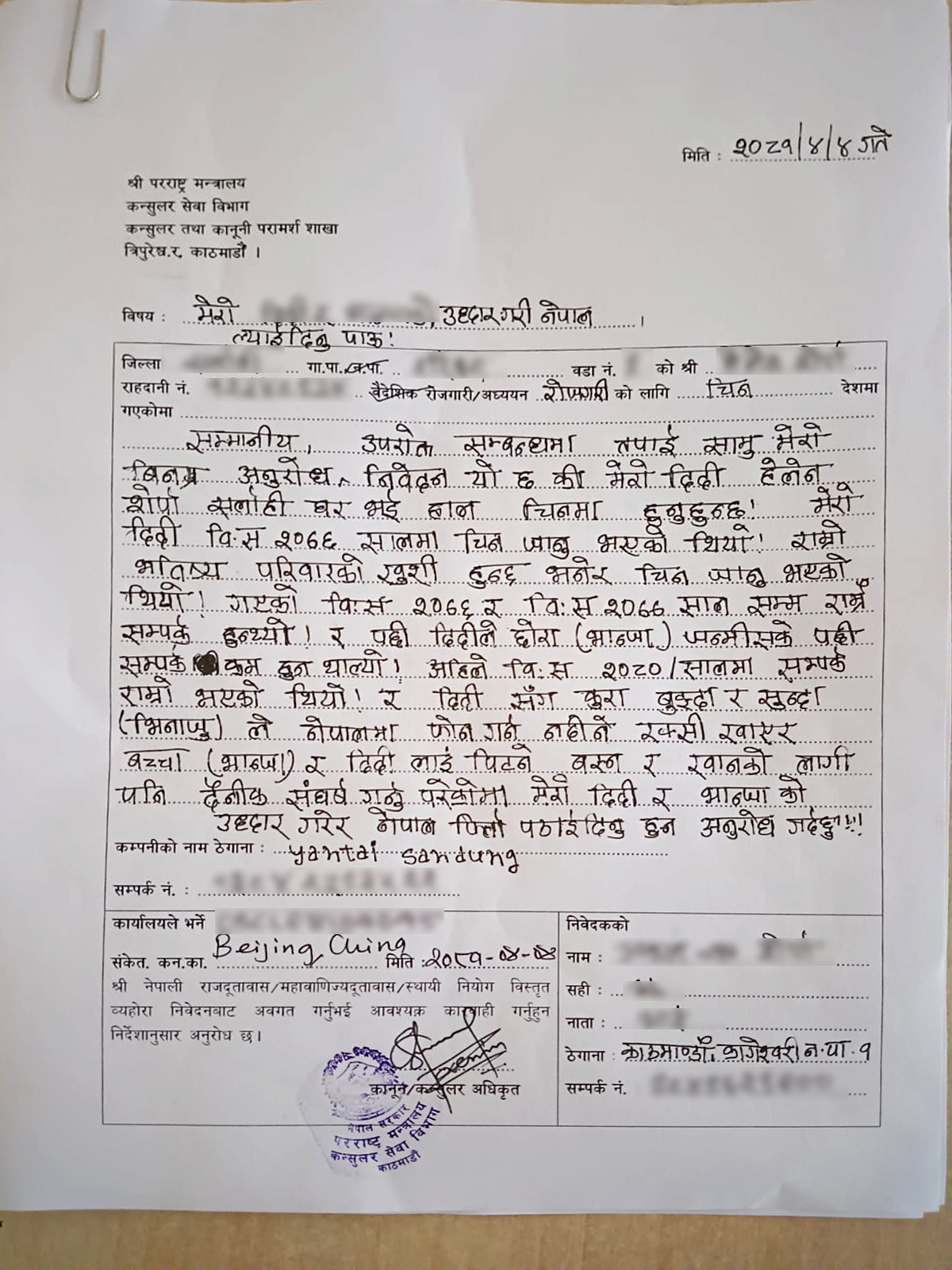

One such case is that of Sapana, a 23-year-old from Gulmi. Lured by traffickers, she was married off to a 57-year-old Chinese man. The traffickers handled all the process, from court registration to passport. But once Sapana arrived in China, unfamiliar with the language and culture, her nightmare began. She was subjected to torture by her husband. Her family has since filed a complaint with the Nepali Consulate, pleading for her rescue and return to Nepal.

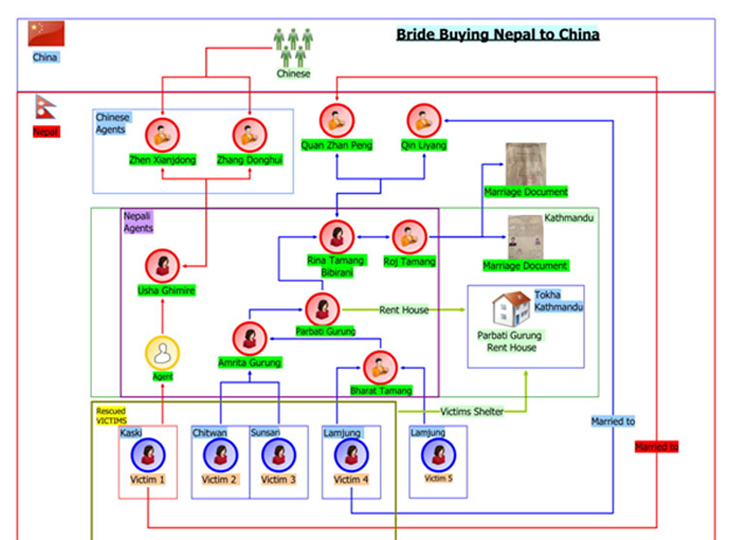

The Trafficking Network

These cases are part of a larger trafficking network operating in Nepal. The traffickers exploit loopholes in "free visa" policies, simplified travel processes, and lenient marriage regulations to traffic vulnerable Nepali women to China. While disguised as legitimate marriages, these arrangements often turn into harrowing tales of abuse and isolation.

No official data exists on the number of Nepali women sent to China through such marriages. Immigration officials admit that since the women travel on "visit visas" for marriage, there is no system to track or maintain separate records. As a result, their stories often remain untold — hidden behind the veil of paperwork that legitimizes their journey but obscures their suffering.

According to the Department of Immigration (DoI), 41 Nepali women who had married and were en route to China in August and September were intercepted at the airport over trafficking concerns. Between mid-October 2023 and mid-October 2024, a total of 184 women were returned from China.

“In recent years, the number of Nepali women wanting to marry Chinese men and move to China has increased,” said Kosh Hari Niraula, a former director general of the DoI.

He said since marriage is considered a personal matter, it is challenging to intervene. “However, after reports of abuse, we have become more cautious. If we spot any suspicious activity during airport checks, we stop them from leaving,” he said. To curb the trend, immigration authorities now require women to acquire a basic understanding of the Chinese language and obtain a No Objection Certificate (NOC) from the Chinese embassy before departure.

Fraudulent Marriages, False Promises

In the last 14 months, 135 Nepali women registered marriages with Chinese citizens in Kathmandu district alone. Since these figures only reflect marriages registered in Kathmandu, the actual number could be significantly higher if marriages registered in other districts are included.

While these marriages are legally registered, immigration officials remain skeptical of the true intentions behind them.

Stories shared by immigration officers point to a troubling pattern of deceit and coercion.

One case involved a shop owner from New Road, Kathmandu, who frequently traveled to China. She employed a 27-year-old woman in her shop and convinced her to marry a Chinese man, promising a life of prosperity. The woman, who had only studied up to the second grade, agreed. The shop owner facilitated the marriage, arranging the woman’s passport, visa, and a meeting with the Chinese man. The two got married within a week. The man returned to China but came back six months later to take the woman with him. However, immigration authorities stopped them at the airport, suspecting foul play.

In another case, a 22-year-old woman arrived at the airport with her Chinese husband. When immigration officers stopped them, she begged to be allowed to leave. An officer told her she could travel once she had a child. Fifteen days later, the couple returned, this time claiming she was pregnant. But when officers examined the medical report, they discovered it was fake.

One immigration officer even recounted the case of a woman who married three different Chinese men. "They have all the required documents — proof of relationship, marriage registration, embassy-issued visas, and even parents coming to send their daughter off with her husband," the officer said. "But despite all this, the intention is often fraudulent."

Middlemen lure vulnerable young women — often poor, uneducated, or from marginalized communities — with promises of wealth and luxury. They arrange meetings, facilitate legal documents, and even handle travel arrangements, making it seem like a legitimate process.

According to immigration officials, discussions have been held with the Chinese Embassy regarding marriage visas. The Chinese Embassy is said to have issued around 200 NOCs for marriages between Nepali women and Chinese men. However, the total number of marriages appears to be closer to 500, suggesting that as many as 300 NOCs could be forged.

Documented cases reveal many Nepali women who marry Chinese men face domestic violence, sexual exploitation, and other forms of abuse once they reach China. In one complaint filed with Nepal's Human Trafficking Bureau, a woman described being subjected to extreme abuse within just 10 to 12 days of arriving in China.

In her statement, she revealed that she was kept and held captive, forced to take stimulating drugs, and compelled to engage in painful sexual encounters for extended periods.

"A few days later, I was left alone in a small hut near my home. I was forced to have sexual relations with 8-10 men daily for money. He threatened to kill me if I refused. I became so desperate that I tried to commit suicide by injuring my left hand with a blade," she stated.

In another case, a woman rescued earlier in July this year, wrote in a letter to the embassy, saying, "I am being held captive here, subjected to cruel and inhumane treatment. I am experiencing extreme mental and sexual exploitation. I am constantly beaten and not allowed to refuse sexual contact." She also complained of severe physical and mental torture, being threatened with death if she attempted to return to Nepal.

The trafficking network's reach extends to child marriages as well. In one shocking case on October 16, local police in Sunsari arrested eight people, including parents from a wedding reception. In Jorpati Rural Municipality-2 in neighboring Dhankuta, a 39-year-old man arranged the marriage of an 18-year-old girl to a 33-year-old Chinese citizen named Li Teng.

According to the Civil Code, the legal marriage age for women is 20. The police registered a marriage-related case in the Sunsari court after the arrest. Following the arrest of the Nepali and two Chinese citizens, police officials have expressed concerns about potential human trafficking.

for arranging the marriage of an 18-year-old girl to a 33-year-old Chinese man. The would-be groom, aged 39, was also taken into custody.

Court records from Kathmandu District also reveal several instances of "unequal marriages," where significant age disparities exist between Nepali brides and their Chinese husbands.

These marriages are often orchestrated by traffickers, who not only promise wealth and security but also engage in financial transactions. It is reported that traffickers charge substantial sums from Chinese men and, in some cases, share a portion of the payment with the women’s families.

On August 29, 2019, the Human Trafficking Bureau arrested 10 individuals, including Chinese and Nepali nationals. Rescued Nepali women reported that traffickers had promised them money. During a police investigation, one Nepali woman revealed that a middleman had demanded up to 1 million rupees for managing her travel to China.

On July 11, the Nepali Embassy in Beijing rescued and repatriated two young women. In a letter to Nepal's Consular Services, the embassy detailed how Nepali women already residing in China had lured these two young women with promises of comfortable life, economic prosperity, and various other enticements, ultimately arranging their marriages to Chinese citizens.

It was found that the Chinese citizen had paid the trafficker Sundari Rai, 115,000 Chinese yuan. In another case, the embassy had rescued and repatriated a young woman from Makwanpur, where a Chinese citizen had reportedly paid 500,000 rupees to arrange the marriage.

After a complaint was filed with the Chinese Embassy about 140 missing Nepali women, the Nepali Embassy in China rescued and repatriated three women. Subsequently, immigration authorities have implemented a policy requiring women seeking marriage-based migration to China to either have a basic understanding of the Chinese language or possess a valid NOC (No Objection Certificate) before being permitted to travel.

A Decade of Marriage Scams

The trafficking of Nepali women to China under the guise of marriage has persisted for at least a decade. On March 6, 2015, Nepal Police’s Central Investigation Bureau (CIB) raided a 'marriage bureau' named Cheru International Pvt. Ltd., operating in Kathmandu. The company was accused of facilitating paper marriages between Nepali women and South Korean and Chinese men. According to police, at least 83 such "marriage bureaus" were active across Nepal, enabling the trafficking of women to South Korea and China in the name of marriage.

Former Deputy Inspector General (DIG) Hemanta Malla Thakuri, who was then the director of the CIB, described it as a thriving industry. "It appeared to be an organized operation," he said. "The scale of this business drew the attention of both our administration and law enforcement agencies.

In response to the growing number of trafficking cases involving Nepali women being sent to South Korea and China under the pretense of marriage, the Nepali government banned marriages between Nepali women and citizens of China and South Korea in 2016. The decision came after reports of abuse, exploitation, and violence against Nepali women married to citizens from these countries.

A Gorkhapatra news article published on November 13, 2016, highlighted the government's rationale for the ban. The article stated, "The dreams of most Nepali girls who marry foreign citizens with hopes of a better future have remained unfulfilled, leading the Home Ministry to ban marriages with citizens of China and South Korea." The report also cited cases of extreme torture, sexual abuse, and domestic violence inflicted on Nepali women married to citizens of these two countries.

However, the ban was short-lived. About two years later, legal reforms altered the marriage registration process. With the introduction of the National Civil Code, which took effect on August 17, 2018, the authority to register marriages was transferred from District Administration Offices to District Courts. This change effectively lifted the ban, allowing marriages with citizens of China and South Korea to resume.

Marriage Market

The scale of the marriage trafficking industry is underscored by a 2013 study jointly conducted by the Migrants Center of Asian Human Rights and the Cultural Development Forum. The study revealed that hundreds of women from rural Nepal were sent to South Korea through "paper marriages." Recruitment agencies charged between 800,000 to 1.2 million Nepali rupees per woman. Of this amount, agents pocketed around 500,000 rupees, while the rest was used for wedding expenses and paperwork.

This "marriage industry" extends beyond South Korea to China. SSP Jeevan Kumar Shrestha, a former head of Nepal’s Human Trafficking Bureau, said traffickers use people involved in business and travel between Nepal and China to facilitate marriages. "We have seen during our investigation that marriages are being arranged by individuals who trade, do business, or frequently travel between the two countries. Their aides play a crucial role in this process," Shrestha said.

A report published by the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) in November 2011 revealed the grim reality faced by many Nepali women married to foreign nationals. Between 2005 and 2013, at least 1,000 Nepali women were sent to South Korea as brides, according to the National Report on Trafficking in Women and Children 2009-2010.

While 300 women reported being satisfied with their lives, the remaining 700 were essentially trapped in slavery-like conditions.

For Nepali women who marry Chinese men, the story is equally grim. Former NHRC member Mohna Ansari described the situation of Nepali women in China as "dire." “The reality of this issue is yet to be fully exposed,” she said. “Many of these women are subjected to extreme torture and sexual exploitation after marriage.”

Ansari’s concerns are echoed by Surendra Kumar Yadav, the acting ambassador at the Nepali embassy in Beijing. He said cases of domestic violence against Nepali women married to Chinese citizens have been reported to the embassy. “These women are brought in with false promises and manipulated into marriage. The environment here is not favorable for them, and many of them face exploitation,” Yadav said. "Within five to six months of their arrival, the majority of them want to return to Nepal."

The trafficking of Nepali women and girls to China and South Korea through the guise of marriage is on the rise, according to the National Report on Trafficking in Persons 2013-15, published by Nepal's National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) in March 2016. The report attributes the surge to low birth rates and a strong societal preference for sons in both countries. At the time, the trafficking of girls from Nepal to South Korea was at its peak, coinciding with South Korea and China being ranked among the countries with the lowest fertility rates in the world.

China and South Korea have long faced a demographic imbalance, with significantly more men than women. This disparity, driven by decades of low birth rates and gender-based preferences for sons, has created a crisis in the marriage market. The imbalance has made it increasingly difficult for men to find wives.

The growing demand for brides in these countries has fueled a transnational trafficking network that preys on women from poorer countries like Nepal. “On one side, there is a high demand for girls to marry in China and Korea, and on the other side, there is poverty and unemployment in Nepal,” the report said. “These two factors have become lucrative opportunities for traffickers and middlemen.”

China's infamous one-child policy (which ended in 2016) and a cultural preference for sons have further exacerbated the situation. As a result, reports suggest that Chinese trafficking networks initially focused on smuggling young women from Vietnam. Over time, this expanded to Myanmar, Cambodia, and other Southeast Asian nations. By 2019, these trafficking networks extended to Pakistan, with reports of vulnerable young women from marginalized communities being trafficked to China.

Trafficking Pipeline

A sensational investigation by the BBC revealed that around 600 young Pakistani women and girls were sold as brides to Chinese men over a two-year period. The report exposed the horrifying conditions these women faced once in China. Many were subjected to prostitution, while others were reportedly killed for their organs, which were then sold in illegal organ markets.

Chetnath Acharya, a journalist who has worked as a foreign expert at China Media Group's Nepali Service for over a decade, highlights the role of cultural shifts and economic pressures in the Chinese marriage market. He said Chinese women are increasingly reluctant to marry, contributing to the marriage gap. As a result, Chinese men, particularly those from lower-income backgrounds, struggle to find local brides.

“The alternative for these men has become Nepali women, who are trafficked to China through marriage brokers,” said Acharya. He added that Chinese marriage customs have become increasingly costly and extravagant. Unlike the Nepali tradition, where a bride’s family typically provides a dowry, the tradition in China places the financial burden on the groom. A prospective groom is often expected to provide a house, a car, and significant financial gifts to the bride’s family.

This custom has made it nearly impossible for poor Chinese men to afford a marriage within their own communities. As a result, they turn to "cheaper" alternatives — foreign brides from poorer countries like Nepal. Marriage brokers and traffickers capitalize on this demand by targeting vulnerable women from economically disadvantaged communities in Nepal.

Each year, a significant number of Nepali women marry Chinese citizens, but the lack of a comprehensive record means the exact figure remains unknown. The scale of the issue is hinted at by official data — 135 women registered marriages with Chinese men in Kathmandu alone over a 14-month period. If similar trends exist across the country, the total number could be much higher.

However, when it comes to rescue efforts, the numbers tell a different story. According to the Human Trafficking Bureau of the Nepal Police, only five Nepali women have been rescued from China. Superintendent of Police Gautam Mishra, the former spokesperson for the bureau, said that only four cases have been officially registered.

Human rights activists argue this discrepancy reflects weak enforcement and inadequate state intervention. Mohna Ansari, a former member of the NHRC, said while China’s image as a land of prosperity is widely publicized in Nepal, the grim reality faced by Nepali women married to Chinese men is largely ignored. She said that Nepal's embassy indifference toward the plight of these women was a sad reality.

On the other hand, Surendra Kumar Yadav, the acting Nepali ambassador in Beijing, claimed the embassy had rescued victims whenever it was made aware of such cases.

Former Deputy Inspector General (DIG) Hemanta Malla of Nepal Police said the Chinese traffickers have exploited the vulnerabilities of Nepali women, especially those who are illiterate, unemployed, or living in poverty. "The government's role is crucial in curbing this trend of luring and trapping innocent women," he said.

“I Don’t Even Want to Remember China” — A Survivor’s Story

I’m 21 now. I never even got to finish my SLC (School Leaving Certificate). Our family's financial situation was terrible. As the eldest of four children, I felt responsible for helping my parents. There was no other choice — I had to find work abroad.

My first experience working abroad was in Oman. When I returned to Nepal, I was still looking for a way to support my family. That’s when I met Sundari Rai. She was introduced to me by a relative. She told me she had lived in China for 20 years and that life there was better. I fell into her trap.

Neither me nor my family got any money from the groom, though. Sundari took all the money herself.

When I arrived in China, things changed almost immediately. The man I had married wouldn’t let me talk to my parents. He started abusing me. The beatings came suddenly, for no reason. I would cry, but no one was there to listen. His family also didn’t seem to care. Even now, I don’t like to think about it (crying).

After I endured the suffering, I was finally rescued. A Nepali woman living in China helped me contact the Nepali embassy. That was my way out. I was finally going home. But I couldn’t actually go home because I had lied to my parents about travelling to China.

I was barred from joining my family and there was a lack of job opportunity in Nepal. So, I moved to Kuwait to work as a housemaid. I don’t want to talk with anyone about my trip to China. Sundari Rai, who trafficked me, has sent many Nepali women to China.

Published in Naya patrika on 7 December 2024

More Investigative Stories

In Ramechhap, entire villages are emptying out as outmigration spikes

Schools, health posts and shops in Ramechhap’s villages are getting lifeless while fields remain fallow. The empty villages are highlighting...

Gender and sexual and minorities: Struggle for identity

People from gender and sexual minority communities have long been denied recognition of their true identity in citizenship and other...

Comment Here