Investigative Stories

Kalpana Sunar, a mother of an 8-year-old daughter from Bachchaud in Humla’s Tajakot-3, arrived at the Nutritional Rehabilitation Home in Surkhet after her daughter’s body weight and height didn’t rise in proportion to her age. Doctors have said that because Kalpana didn’t consume nutritional food during pregnancy, its effect is seen on her daughter.

According to data from Provincial Health Directorate, the provincial and federal governments have invested as much as Rs 1 billion 30 million in five years between mid-June 2019 and mid-June 2024 to improve nutrition intake among children in Karnali. But authorities have identified as many as 52,440 children with malnutrition in five districts of Karnali—Kalikot, Jumla, Humla, Mugu and Dolpa—during the five-year period. They have identified a total of 26,442 children with malnutrition in the province’s districts with no such nutrition-focused programmes under the budget—Surkhet, Salyan, Rukum, Dailekh, Jajarkot. These districts, however, have seen the ‘Balvita’ programme launched at all of their local units since 2012. Under this programme, children between the age of six months and 23 months are fed the nutritional lito called ‘Balvita’.

Kalpana says her 8-year-old daughter weighs only 4 kg. “I have received nutritional flour from health organisations only twice,” she says. “I can’t feed her anything nutritional at home.”

A ‘Mother and Child Health and Nutrition Programme’ was launched in Karnali’s five districts in collaboration between Nepal government and the UN World Food Programme. Other programmes with similar goals are also launched in the province. But data from the directorate shows that a total of 23,869 children up to 11 months of age and 28,571 children between 12 months and 23 months are found to be malnourished. For the Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Programme alone, the Ministry of Federal Affairs and General Administration has spent a total of Rs 593 million 464 thousand between fiscal years 2077/78 and 2080/81.

Like Kalpana, Saraswati Devkota of Sannitriveni-3 in Kalikot is also currently at the nutritional rehabilitation home for her son’s treatment. Saraswati, who has visited the rehabilitation home repeatedly, says that there’s nepotism in the distribution of nutritional food in the village. “When you are delayed by a day, the officials say the nutritional supplement is over,” she says. “What’s the use of the programme that doesn’t distribute it to those who need it? We need to know how the money meant for the programme is spent.”

The community health unit in Luyata lies about a four-hour walk away from Saraswati’s home. Before she can manage to reach there, she gets the news that the supplement is finished. While the government claims it is sending the nutritional supplements to remote villages, the locals have to visit hospitals at cities as they can’t access the food.

Nimalajum Bhote, a local of Dho in Dolpobuddha Rural Municipality-1, says she received the nutritional supplements only about six or seven times over the 17 months of her postpartum period. She was supposed to receive it once every month. “The officials do not provide it to us under various pretexts,” she says. “Sometimes they say they don’t have enough manpower, other times, they say they have a shortage.”

Dr Nawaraj KC, a pediatrician based in Surkhet, says that there is a gap between the investment that the state has made to reduce malnutrition and the work that is actually being done. “This seems to have benefitted the companies that sell nutritional supplements, not the children born in impoverished families,” KC says. “It should be investigated why the programmes with millions of investments have not yielded the desired results.”

KC adds that authorities should understand that the malnutrition problem is so widespread in Karnali because the people here lack awareness about food and nutrition. “In Karnali, child marriage and teenage pregnancy is still rife,” he says. “Moreover, Dalit children suffer from malnutrition the most.”

Until issues of child marriage and poverty are not addressed, it’s hard to curb malnutrition by distributing nutritional flour alone, KC says.

The Province Health Logistics Management Center, Surkhet spent Rs 146 million 800 thousand in supplying nutritional flour in fiscal years 2079-80 and 2080-81 BS. The centre hasn’t issued a tender after a case was filed at Commission for Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA) alleging there were irregularities in the tender process. In the five years, the centre has spent Rs 403 million 676 thousand in the distribution.

But the directorate’s data shows that the number of children with malnutrition has not declined. While the number was 9584 in fiscal year 2076-77 BS, it was 9469 in 2080-81 BS. In five years, the number of children within 11 months who are at critical risk due to malnutrition is 23,869, while the number of those between 12 months and 23 months is 28,571.

The government had launched the programme in 2070 BS. According to which, the government provides postpartum women and children between 6 and 23 months of age with nutritional flour at 148 health centres in five districts of the province.

Programme officer Samikshya Acharya of the health department under the provincial Ministry of Social Development says that data shows the nutrition intake among children in the province is miserable. “Children are suffering from stunting and growth disorder, while teens and women are suffering from malnutrition and anemia,” Acharya says.

No improvement despite huge investment

Data from Health Office Kalikot shows that as many as 1039.7 metric tons of nutritional supplements were distributed in the district in the past five years. This is higher in comparison to other districts of the province. The nutritional flour is distributed from 73 health units in the district. The District Hospital Kalikot has claimed that the programme has benefitted an average of 7,650 women and chlidren in a year. But the flour is distributed in only eight months as it is not supplied to the district, according to Katak Mahat, information officer of Kalikot District Health Office. “We don’t know what happens to the flour meant for the district for four months,” Mahat says. Over five years, there has been only a slight decline in the number of children suffering from malnutrition in the district, from 1,770 in 2077-78 BS to 1,669 in 2080-81. Meanwhile, in districts such as Jumla, Humla and Dolpa, the number has risen in the period.

Parbati Singh, deputy chair of Kalikot’s Sannitriveni Rural Municipality, says that many postpartum women have arrived at her office with grievances that they haven’t received the nutritional flour. “But the health offices claim that they have provided the flour to the women monthly,” she says. “But women say they haven’t received it. It looks like the officials are themselves engaged in irregularities.”

The CIAA’s Surkhet branch is currently investigating irregularities related to the programme. “We are investigating possible corruption on the purchase of the flour after 2078 BS,” an official at the CIAA says.

Ramlal Devkota, chief of the Madana Health Centre in Humla’a Tajakot Rural Municipality, says that the flour is not supplied between Asoj and Falgun. “After snowfall, the air travel gets halted, and so does road transportation,” Devkota says. “That’s why flour is not distributed for six months.” According to him, while the government and INGOs who coordinate the process claim that the distribution is smooth, the reality is otherwise.

Senior Public Health Officer Karuna Bhattarai of Province Health Directorate says that poverty, child marriage and lack of hygiene have contributed to the rise in malnutrition in Karnali. “Distribution of nutritional flour is not enough,” Bhattarai says. “Programmes focusing on adolescents are also essential. For many postpartum women, visiting the Nutritional Rehabilitation Centre is not always feasible.”

According to Man Kumari Gurung, senior community nursing officer at the directorate, lack of awareness is the main culprit behind the rise in malnutrition. “Lack of enough breastfeeding is another reason,” she says. “Many children in Karnali are malnourished and hence their mental and physical development is stalled.” Gurung further said that they haven’t been able to distribute the nutritional flour on a monthly basis due to a lack of budget and are distributing it in an interval of three-four months.

The government has launched as many as 16 programmes focused on reducing malnutrition among children in Karnali. There are Nutritional Rehabilitation Centres in Surkhet, Dailekh and Jumla. But these efforts have not yielded the desired results.

Dr Aruna Uprety, a public health expert, says that distributing nutritional flour alone is not enough to curb malnutrition. “Nutrition is a matter of development priorities. It’s not just about food,” Uprety says. “The Karnali government has not been able to establish nutrition as a major agenda.”

Uprety adds that even junks like ‘Balvita’ are being offered in the name of distributing nutritious food. “The focus should be instead on raising awareness about diet habits and local products,” Uprety says. “When I was in Mugu, I saw rotten flour being distributed as nutritional food. The situation of all rural districts in Karnali is the same.”

More Investigative Stories

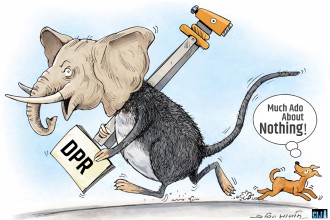

Nepal’s local governments have spent Rs1.5 billion in DPRs. Has it all gone to waste?

Many detailed project reports (DPRs) are neither on record nor have the proposed projects taken off. CIJ Nepal investigates what...

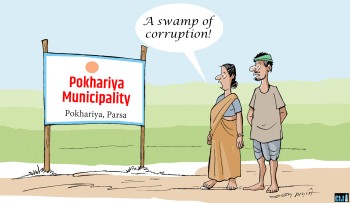

Pokhariya Municipality: The local government that has become the hotbed of organised corruption

The local government has witnessed illicit transfer and appointment of hundreds of officials. Many say they had paid for the...

Comment Here